Using Wills and Probate Records in Genealogy Research

Using wills and probate records for genealogy can lead to unexpected “inheritances” of your own: clues about relatives’ identities, wealth, personal belongings, and family relationships. Wills can reveal great family stories, too: researcher Margaret Linford entertains her mother with them during trips to the courthouse. Here’s how wills can help your family history—and Margaret’s tips for finding and using them.

Using Wills and Probate Records in Genealogy Research

“Where there’s a will, there’s a way” to find out more about your family’s history.

Wills are legal records created to direct the settlement of a person’s property and other final affairs after his or her death. Probate (or estate) records are created after an individual’s death as part of the legal distribution of the estate and payment of debts. You’ll often find wills as one of many kinds of the documents included in probate records.

Wills and other probate records are valuable research tools, but are frequently neglected as sources of genealogical information. People often focus strictly on birth, marriage, and death records when searching out their family histories. If you rely solely on those records, your research will encounter many brick walls in the early 1800’s.

Probate records and land records were often the only official documents left behind to tell the stories of ancestors who lived prior to the legal requirement for the registry of births and deaths.

Wills of slaveholders can also be valuable tools in conducting African-American genealogical research. Before the Civil War, enslaved people were listed in wills because they were valuable property of slaveholders.

For instance, in the 1863 Smyth County property tax records, it is noted that Abijah Thomas owned 56 slaves, which were valued at $53,800. Some were given their freedom within wills, while others were transferred to other members of the family or sold. For instance, one of the first wills recorded in Smyth County is that of Hugh Cole.

Within his will, he says the following: “I bequeath to my beloved wife Martha Cole a negro girl named Amanda which she is to hold during her natural life.” The mention of an enslaved person in a will—along with any personal description of him or her—may be the only surviving document to mention that person by name.

Within another Smyth County will, recorded on February 20, 1835, a woman named Elizabeth Blessing left the following directive: “I will and desire that my negro woman Betty be free at my decease, and must see to her own support during her life, as I shall not make any provision for her out of any part of my estate.”

Information Found in Wills Varies

You can find just about anything in a will!

One organ, one compass, chain and plotting instruments, two chests, one hat rack, one music rack, one old United States map. These are some of the items found in the appraisement bill of the personal property belonging to the estate of Abijah Thomas, who lived in the well-known Octagon House in Marion, Virginia.

Here is a photo of that home, now in a dilapidated state, from a Wikipedia file image (click image for attribution.)

Also included in his personal property is a church bell. The story behind the bell is intriguing and illustrates the significance of the probate process.

Abijah Thomas utilized the bell at his foundry works in Marion, Virginia, to indicate shift changes. For decades, the oral history surrounding the bell indicated that he had donated it to the Wytheville Presbyterian Church before he died. The court documents reveal a different story.

Court document regarding the church bell

Since Abijah died intestate, the court appointed three men to appraise his personal property. During this process, the bell was valued at $75. It was sold on September 1, 1877, to the Presbyterian Church in the town of Wytheville, Virginia, as shown in the above list of items sold from his estate.

This document dispels the family myth surrounding the church bell. This is just one of many examples of the types of stories you find in probate records in courthouses all across the United States.

Genealogical Information May be Found in a Will or Probate Records

Wills and probate records can pass along unexpected genealogical wealth to you. You may find the following information in them: date of death (or approximate date of death), name of spouse, children, parents, siblings and their place of residence, adoption or guardianship of minor children, ancestor’s previous residence, occupation, land ownership, and household items.

Probate records also contain such interesting stories that they can even be read for entertainment!

Whenever I go on a research trip, I usually drag some poor, unsuspecting soul along with me. That person is usually my Mom. While she enjoys the scenery on our drive to different courthouses, she rarely enjoys the time spent at the courthouse.

Some of the research I do requires me to stay at the courthouse for several hours. That has posed a problem in the past since I haven’t known how to keep Mom occupied. But I have found the perfect solution. When we arrive at the courthouse, I find an old will book and let her start reading.

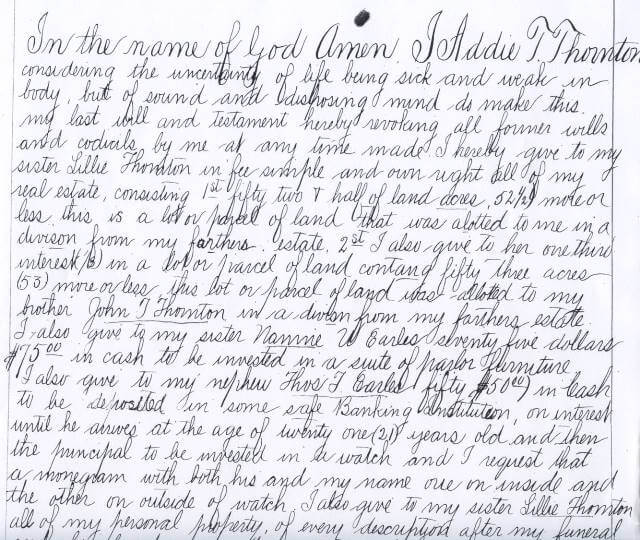

My mom enjoys reading the stories in these old—and sometimes tattered—books. One of her favorite stories came from a will in Henry County, Virginia. It is the will of Addie T. Thornton and reads as follows:

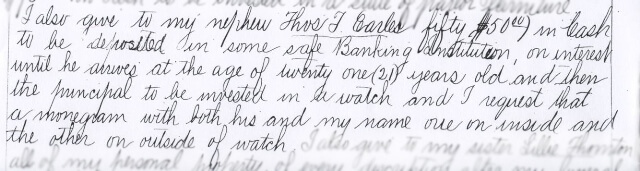

“I also give to my nephew Thomas T. Earles, fifty ($50) in cash to be deposited in some safe Banking Institution, on interest until he arrives at the age of twenty-one (21) years old and then the principal to be invested in a watch and I request that a monogram with both his and my name, one on inside and the other on outside of watch.”

Obviously, Addie Thornton cared deeply for her nephew, Thomas, and wanted to make sure he remembered her for the rest of his life.

Here’s part of Addie’s will, followed by a closeup image of the lines about the watch:

Stories like these are so much more meaningful than just a date of birth, marriage or death. Wills can help us know who these people were, how they lived and what was important to them during their sojourn here on earth. We can learn of their struggles and their successes. We can tell what their lives were like by reading through the lists of household items included in the inventories that are recorded.

And with stories like Addie’s bequest of the watch, we can also learn about ancestors’ personalities and how they expressed (or occasionally withheld) love for others through the final disposition of their belongings.

How a Will is Created

Before beginning probate record research, it is important to be familiar with the probate process and legal terminology associated with these records. It is estimated that, prior to 1900, about half of the population either left a will or was mentioned in one. Those who died having left a will are said to have died “testate.” Those who died without leaving a valid will died “intestate.”

A typical, legally-recognized will contains certain critical elements. It should be in written form and it must have signatures of the person leaving the will (“testator”) and witnesses, who attest to the validity of the document. A codicil is a document created by the testator to amend the will.

Once the testator dies, the will is presented to the judicial authority by a family member or executor/executrix (person appointed by the testator to see that his/her wishes are carried out), accompanied by a written application or petition for probate.

These petitions include names and addresses of the closest living relatives. The court then admits the will to probate and sets a hearing, providing an opportunity for interested parties to contest the will. The will is then recorded and the executor is given the authority to settle the estate. During this process, an inventory of the estate is made.

Some wills contain detailed information, regarding the testator’s final wishes. At times, these requests will shed light on relationships that might not otherwise be discovered. This was the case for a will on file at my local courthouse. Due to the nature of the requests made by the testator, I have changed the last name of the family to Smith. This wife was, obviously, upset with her husband and the circumstances of their marriage, providing clear details of her grievances for future generations.

“Since my husband has never made me a part of his family and has completely cut me out of ever living in Chihowie, Virginia [the husband’s hometown], or never provided me with a home or paid any of my bills and has broken all marriage contracts that we agreed to—I hereby decree that I be buried in Round Hill Cemetery at Marion, Virginia, where I own a lot—that my body or anything I own or possess will never be taken into Chilhowie or the Smith household.

My husband has never taken me into his own home, and furthermore stated, backed up by his nephew and his wife, whom he turned everything over to shortly after our marriage—that I would never own or live on a foot of the Smith ground, even though I have tried to build or buy or remodel a home in Chilhowie, Virginia, at my own expense.

“I give all books and material things pertaining to books to the Smyth County Library, Marion, Virginia, as I am sure that my family would not want anything to fall into the hands of anyone who has mistreated me.

“My husband has kept our marriage strictly on a time clock basis since his nephew and his wife moved back to Smyth County, and under their influence he comes at 6:30 or 7:00 p.m. (whichever is convenient to them) or later, and leaves promptly in the morning by 8:00 or 8:30 a.m., never calling during the day or show[ing] any sign of caring. He changed completely after they returned to Chilhowie to break up the marriage. Therefore, if I am still his wife, or otherwise, see that my wishes are carried out and that my remains and possessions remain in Marion.”

Where to Find Wills and Probate Records

The best place to search for a will is at the courthouse where your ancestor lived, if you can reasonably go there yourself.

Since the probate process is a function of state governments, the laws governing the maintenance of these records and their location will vary by state and should be researched before making a trip to the courthouse.

For example, in Virginia, probate records are maintained within the Circuit Courts and independent cities. In Massachusetts, probate records are found in county Probate Courts.

A useful resource for figuring out how U.S. probate records are organized state-by-state is free on the Ancestry.com wiki: Red Book: American State, County and Town Sources. Scroll down to click on the name of the state in question. Then go to the right side and click on the probate records link for that state to read about these records.

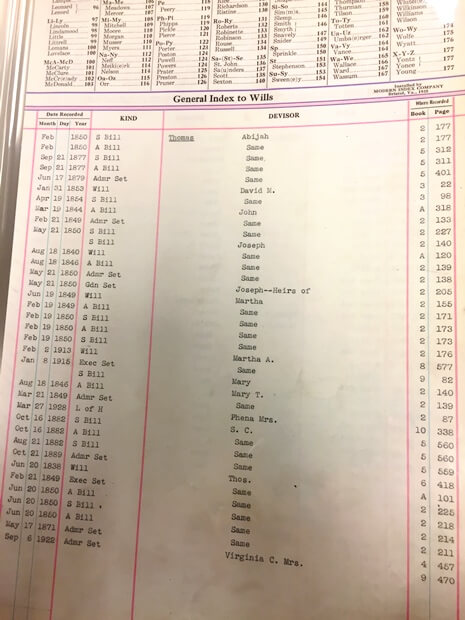

Once you have determined where the wills for your state/county are housed, the next step in the research process is to locate the Index for Wills. Even–perhaps especially–if you are unsure of the date of death for one of your ancestors, you may want to look through the index of wills (an example is shown here). Even when no specific death record exists, you may be surprised to find probate records that reveal the date of death, a list of heirs and more.

There will, most likely, be several index books, organized by year spans. These books serve as a compass, pointing you to any available probate records that may include your ancestors. The index is divided by devisor (the person making the will) and devisee (any person who is named in the will, as the recipient of property).

The research process will be incomplete if you do not conduct a search for your ancestors among the list of devisees. Even if you fail to find their names among the devisors, they could have inherited property from someone else.

Probate records include more than just the will of an individual. You may find letters of administration, lists of heirs, inventories, bills of appraisement, guardianships and other documents related to the settlement of an estate. In some counties, all these documents are found in the same collection. Other counties maintain these records in separate collections. It is important to understand the manner in which probate records are organized for your particular county.

The probate research process should not be rushed. Valuable records may be overlooked when time dictates the quality of your research. For this reason, it is important that you set aside ample time to comb through the probate records. If you find yourself confused about abbreviations or the location of records within the courthouse, there is usually someone in the records vault who would be happy to assist you. Never be afraid (or embarrassed) to ask for help.

Fortunately for many of us who can’t easily get to every ancestor’s courthouse, there are some wills available online on genealogy websites, including two of the genealogy giants, FamilySearch and Ancestry.com.

For example:

- Subscription website Ancestry.com has made it a priority to curate an enormous collection of wills and probate records from all 50 states. At last count, this collection has more than 170 million records—and they keep adding to it.

- The free FamilySearch.org hosts millions of probate records from the U.S. and around the world (click here to browse their probate and court record collections). Many of these collections are marked “browse-only,” which means they are not yet searchable by name online. You just have to page through them. Click here for instructions on reading browse-only records on the site (it’s not that difficult—and did I mention they’re free?).

Additionally, libraries or genealogical societies in your ancestor’s hometown or county may have books with abstracts from local wills or other resources related to local probate record research.

General Index to Wills

Well Worth the Effort

Finding the will of one of your ancestors is an amazing experience. Walking into the vault of a courthouse sometimes feels like walking into a time machine. As you read through the pages that tell of people who lived so long ago, you feel like for even just a small moment that you have gone back in time. You are sitting with them and hearing their stories whispered through the aging and brittle pages that have been left behind. They are all there just waiting to tell their stories. So take the opportunity to go to the courthouse and “meet” your ancestors through the one of the last—and perhaps one of the most revealing—documents they may ever have written: their wills.

Researching Wills and Probate Records: Your Next Steps

Take your genealogy research to the next level by planning a trip to a courthouse to retrieve records like wills and probate records. These articles and podcast episodes will help you get ready:

- Why you should be researching court records

- Success story: Genealogy research trip produced amazing family history find

- Premium Podcast Episode 128: Courthouse research tips (for Genealogy Gems Premium subscribers)

Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links and Genealogy Gems will be compensated if you make a purchase after clicking on these links (at no additional cost to you). Thank you for supporting Genealogy Gems!

Margaret Linford is a professional genealogist who specializes in the Mid-South Region of United States research and has logged over 20,000 research hours. Born and raised in Virginia, she has enjoyed traveling the world, and now lives in her childhood hometown with her husband and children. She enjoys teaching her children about heritage, taking them along on research trips and serving as President of the Smyth County Genealogical Society.

Find US Ancestors In These New Online Resources

See if you can find U.S. ancestors using these new online resources (many of them free!): U.S. Supreme Court cases; an African American research guide; newspapers serving Illinois, Iowa, North Carolina and Texas; orphan train riders and Rhode Island burials since...Genealogical Evidence and Proof: How to know if you’ve compiled enough evidence

The Genealogical Proof Standard tells us that we need to conduct reasonably exhaustive research in order for our work to be credible. If you’ve ever wondered just what constitutes “reasonable” (and if your family tree is up to snuff) my guest author Kate Eakman, professional genealogist at Legacy Tree Genealogists, has answers.

Professional Genealogist Kate Eakman explains evidence on the Genealogy Gems blog.

Genealogical Evidence: Have You Got What It Takes?

How do we know when we have compiled enough evidence to constitute proof?

Is a birth certificate or an autosomal DNA test result sufficient to declare this person is the child of that person?

Must we collect every record regarding an individual – the deeds, the tax lists, the newspaper clippings, the census reports – before we can declare a familial connection?

The Genealogical Proof Standard (GPS)

The Genealogy Proof Standard (GPS) directs us to perform reasonably exhaustive research, which requires that we identify and review all available records related to an individual.[1] This is being as thorough and accurate as possible and is a goal toward which we should all aspire in our genealogical research.

But, let’s be honest: most of us do not want to spend weeks or months (or even years) documenting one person before moving on to the next individual. We don’t want to know every detail of grandpa’s life before we turn to grandma.

We want to build a family tree which accurately provides us with the names of our ancestors so that we can identify our immigrant ancestor, or join a lineage society, or enjoy the satisfaction that comes from a balanced tree extending back a hundred years or more.

We want to be thorough and accurate, but we also want to make some progress. How do we balance the need for accuracy with the desire for results? How do we determine the necessary quality and quantity of evidence for our research?

Below are some guidelines to demonstrate how we can go about compiling the necessary information to say with confidence “this person is my ancestor.”

Genealogical Evidence Guidelines

1. One record/source is never enough.

Any one piece of data can say anything. A mother might lie on her child’s birth certificate for a number of reasons. A grieving spouse might not correctly recall the information for a husband or wife’s death certificate. There are typos and omissions and messy handwriting with which to contend. Even a lone DNA test is not sufficient evidence to prove a family connection.

We need multiple sources, and different kinds of sources, which corroborate the details of the others.

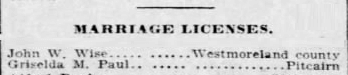

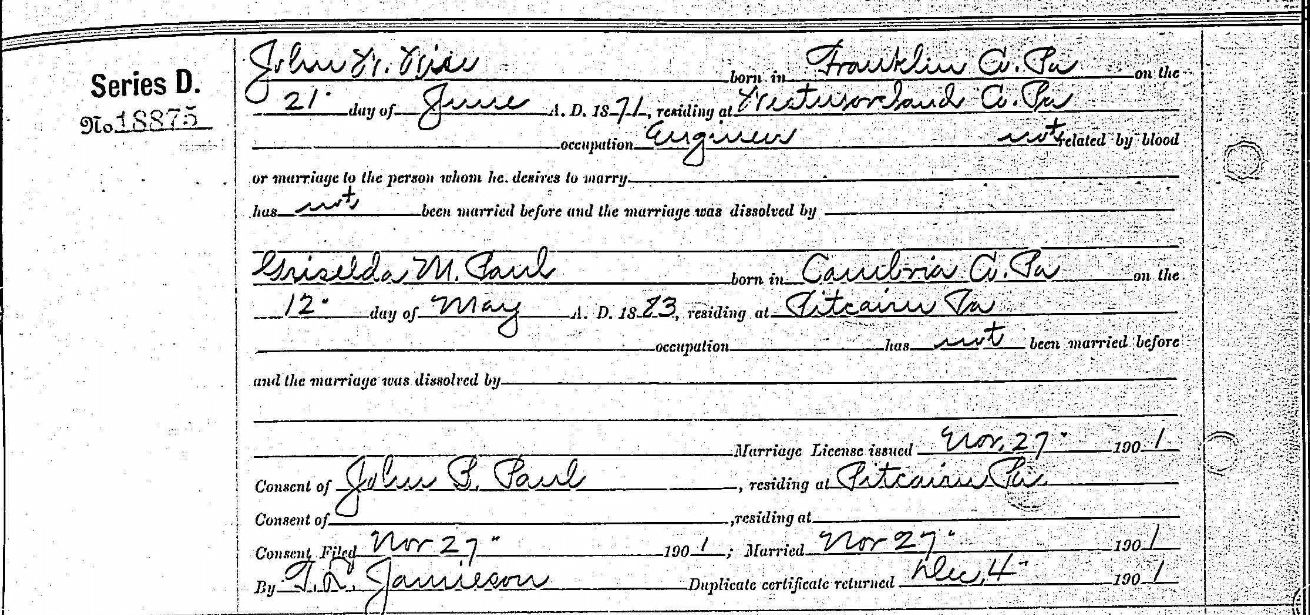

A single source is not enough. A marriage license does not guarantee that John and Griselda married. Photo courtesy https://newspapers.com.

A census report and autosomal DNA test results.

A deed and a will.

A birth certificate and an obituary.

Or, better still, a birth certificate, a census report, a deed, a will, an obituary, and autosomal DNA test results.

2. The more contemporary the source is to the person or event in question, the better.

Records of events made immediately after the event tend to be more accurate, and provide better details, than records created months or years later. As time passes, details become fuzzy, two events can be confused with each other, and our memories fade.

The passage of time between an event and the record of the event also allows for some revisionist history to creep in.

Here are some examples:

A birth year is adjusted to make someone appear older or younger in order to avoid the draft, enlist in the military, mask a dramatic age difference between spouses, or conceal an out-of-wedlock birth.

An obituary ignores the deceased’s first marriage because of some embarrassment associated with that marriage.

A census report enumerates everyone in the household as natives of Stepney, London, when they really were born in Stepney, and Hackney, and Whitechapel, which explains why the baptismal records can’t be found in Stepney.

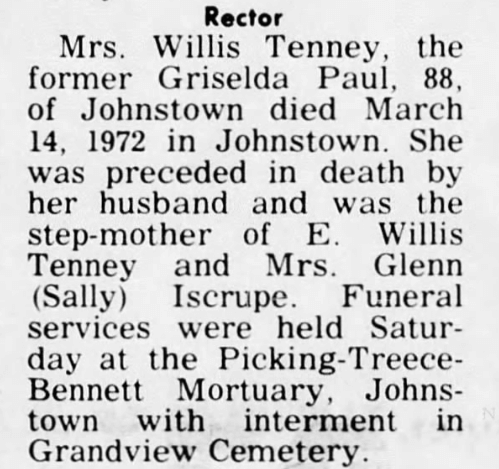

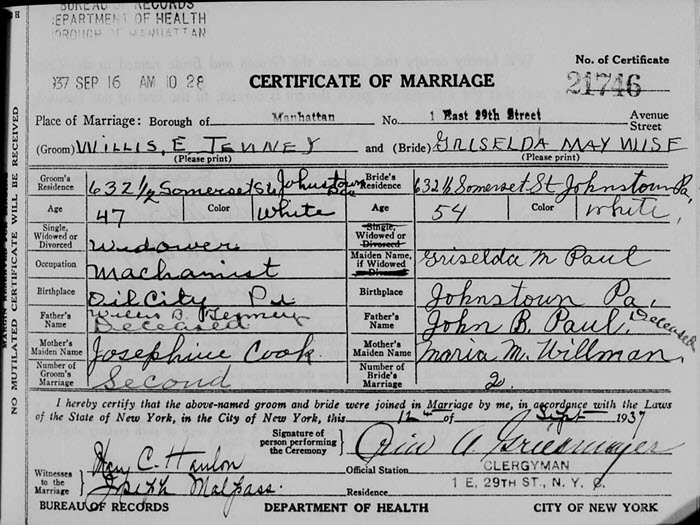

According to this obituary for Griselda, she was the widow of Willis Tenney, not John Wise. It appears Griselda and John did not marry after all. Photo courtesy https://newspapers.com.

According to this obituary for Griselda, she was the widow of Willis Tenney, not John Wise. It appears Griselda and John did not marry after all. Photo courtesy https://newspapers.com.

This is particularly true when it comes to autosomal DNA testing. My autosomal DNA is more useful for identifying my ancestors than is my son’s because I am one generation closer to those ancestors. This is the reason we encourage people to test the oldest members of their family first: their DNA has the potential to be the most useful simply because they are from an earlier generation (or two).

3. It is okay to make appropriate assumptions, but be careful!

In genealogical research we must sometimes make assumptions. When research theories are based on logical reasoning, it is perfectly acceptable to make those appropriate suppositions.

Determining which assumptions are appropriate can be simple: the two-year-old child enumerated in the home of a 90-year-old woman in the 1850 census can safely be eliminated as a biological child of that woman; the man born in 1745 could not have been buried in 1739; the person with whom I share 3150 cM of DNA is my sibling.

The challenge is to avoid making what seems like an appropriate assumption but is really based on faulty reasoning or bias. For instance, we presume that every child listed in a household in the 1860 U.S. Census is son or daughter of the two adults listed first. However, the household could include step-children, cousins, or individuals not even related to the family who were erroneously assigned the same surname.

Other inappropriate assumptions can include:

- the notion that a baby was born within a week of his baptismal date;

- a woman’s reported surname on her marriage certificate is her maiden name;

- there is only one person in any village, town, or city with the name of your ancestor;

- someone who shares 2000 cM of DNA with you must be your grandparent, aunt or uncle, niece or nephew, half sibling, or grandchild (they could be a ¾ sibling, the child of one of your parents and the sibling of the other parent).

4. All of the data from the various sources must correlate, and there can be no unresolved contradictions.

When the birth certificate says Richard was born in 1914, the 1938 newspaper article about his wedding reports Richard was 24 years old and the 1942 World War II Draft Registration card notes Richard’s date of birth occurred in 1914, we can confidently declare Richard was born in 1914.

If the wedding article declared the groom was 23 years old the contradiction could be explained by the time of year in which the wedding occurred – before or after Richard’s birthday.

But if his birth certificate reported a 1914 birth, and the newspaper article noted Richard was 32 years old, while the World War II Draft Registration listed his year of birth as 1920, we have some important contradictions. It is most likely the records are for three different men with the same name.

By collecting additional evidence, we finally learn that Griselda and John Wise did marry, and after his death Griselda married Willis Tenney. If we had collected only one of these four records we would not have had the most accurate information regarding Griselda Paul. Photos courtesy https://familysearch.org.

It’s important to remember that once we have accomplished that initial goal of building out our tree a few generations (or identifying our immigrant ancestor, or determining if we are related to that historical person) we can – and should – go back and collect other sources related to that person. This will result in uncovering a more complete story of their lives in the process.

As we can see from the four documents regarding Griselda Paul’s marriages, her story is much more than a simple list of birth, marriage, and death dates. As we identify, review, and analyze the other available sources, Griselda’s story will come alive with the facts and details we uncover.

A Fresh Set of Eyes on Your Genealogy Brick Wall

Sometimes the wrong evidence or assumptions can push us into a brick wall. A fresh set of expert eyes can help you identify the problem, and recommend the sources you need to pursue in order to compile trustworthy evidence.

If you are looking for some assistance in your genealogical research, Legacy Tree Genealogists can help. Our affordable ($100 USD) Genealogist-on-DemandTM Virtual Consultation service provides you with the opportunity for a 45 minute one-on-one discussion of your research with one of our expert genealogists. We can help guide you in evaluating evidence and determining research strategies to move forward with your research confidently.

About the Author: Kate Eckman

Legacy Tree guest blogger Kate Eakman grew up hearing Civil War stories at her father’s knee and fell in love with history and genealogy at an early age. With a master’s degree in history and over 20 years experience as a genealogist, Kate has worked her magic on hundreds of family trees and narratives.

Professional Genealogists Kate Eakman

[1] “Genealogical Proof Standard (GPS),” Board for Certification of Genealogists, https://bcgcertification.org/ethics-standards, accessed March 2020.