1950 US Census Indexing with FamilySearch

The 1950 census must be indexed so that we can search for relatives by name, location and much, much more. You can help with this exciting project, and no special skills or background are required. Jim Ericson of FamilySearch 1950 Census Community Project explains what’s happening and how you can get involved.

Lisa: The 1950 US federal census was released by the National Archives just a short time ago on April 1 2022. But it was just a release of the digitized images of the census pages. The indexing of those records happens afterwards. It’s really the indexing that makes it possible for all of us to be able to search the records and find our families. Here to tell us about that really important indexing project. To get all this done is Jim Ericson from FamilySearch. They are heading up this project. Welcome, Jim.

Jim: Thank you, Lisa. It’s wonderful to be here with you today.

Lisa: I know you guys are so busy. You’re right on the heels of Rootstech which just wrapped up. And now we’re here with the release of the US Federal Census for 1950! Do you have somebody you’re looking forward to seeing in that census record?

Jim: Yeah, both of my parents will be there. My dad will be 20 years old. He turned 21 that year after the census. And my mom is 15, she will just have had her 15th birthday.

I know where my mom was. She was in Salt Lake City. But I have no idea where my dad was in 1950 as a 20 year old. He’d left college and I know that he had enlisted in the in the army. But I don’t know. He also worked in San Francisco for a couple of years. I don’t know if he’ll be in San Francisco, or where exactly where he would have been in 1950 when the census was taken so there’s a little mystery right there.

Lisa: Absolutely, and that’s a perfect example of why the indexing is so important, because you’ll be able to name search for him when this is done.

The History of FamilySearch

(2:07)

Before we jump into that indexing project, for those who maybe aren’t familiar or haven’t used FamilySearch, tell us what familysearch.org does and what it offers the genealogist.

Jim: FamilySearch is a nonprofit organization. We were founded in 1894 as the Genealogical Society of Utah.

FamilySearch is more of a recent incarnation of the organization that kind of reflects when we went online, and when we started publishing CD ROMs in the 1990s.

We’ve been microfilming and digitizing records since 1938. We started a worldwide project to go and collect records from around the world. Microfilm was really the innovation that allowed us to store all those records in a library. Getting a whole bunch of books or physical records in one location was difficult.

Since then, all of our record operations are now digital. All of our records are captured digitally now. We have worldwide operations in hundreds of countries. We publish over about a billion records a year.

As a nonprofit, we partner with commercial entities who have an interest in profit, because we know that they know how to innovate. And that also helps our resources go further through partnerships with these commercial entities. The 1950 census is actually an example of that sort of a partnership. We’re working on this with Ancestry and using the resources that they have.

FamilySearch has a collaborative family tree where you can see what others know about your family. We have, like I mentioned, 10 billion records that are online. We have free resources to learn how to do family history. And we really try to just bring people wherever they are, to the experiences that can help them learn about their family.

(04:32)

Lisa: It’s amazing how much it’s grown! I remember the days of the CD ROMs with the record sets that we used to order. And now so much is available for free from home. Users just need to sign up for a free account to use the website and take advantage of the records. And I love the Wiki. It’s such a wonderful treasure trove of knowledge when it comes to genealogy research

Let’s talk about the most exciting and the newest record collection, which is the 1950 census. When it was released by the National Archives did you get all the images? Does that mean instantaneous publication on familysearch.org? How did that work initially?

Jim: Well, 10 years ago, in 2012, when they released the 1940 census, we were actually waiting at the National Archives with a van and hard drives. We had to transfer all the data onto hard drives and take them to our data facility in Virginia.

This time, everything was available online. Everything was downloaded and uploaded to our servers immediately. There was high demand. So that was one of the challenges that we faced was making sure that we’re going to be able to download those images, over 6 million images is a lot of images to be able to download. And those images include records for 151 million people. So that’s a lot of information at high quality, resolution. So that was actually the first hurdle.

And since we are doing this project with Ancestry, we also have to wait for Ancestry to do the same thing and download the images, to be able to process them to create their computerized index with their own handwriting recognition technology that then comes to us. It makes it so much easier to review an index as opposed to starting with transcription from scratch. So, there are so many innovations that have taken place. But from the National Archives, the online delivery of images was one of those innovations.

Lisa: How fantastic to be able to do that online. I can imagine that speeding it up. And then you’ve got artificial intelligence, which is already impacting how we use genealogy websites, how we access digitized books, and here you are using it to help index the records.

(7:28)

I’d love to know kind of a comparison between the speed at which you indexed the 1940 census which I thought was pretty darn quick to how that looks for 1950.

Jim: There is a great question, and we’re still learning how this is going to play out with the 1950 census.

The history of census indexing by FamilySearch

(7:54)

One of the first projects that we did as FamilySearch when we were publishing, CD ROMs was the 1880 census. The 1880 census took us more than a decade to press on to CD ROM. It was a huge project! It was crowd sourced, but before the advent of the internet. It was sending packets and physical papers around and then gathering them and then creating a CD ROM.

We went from a project like that, to doing the 1940 census just over a decade later in a matter of about six months. So already the technology was just astounding because of what you’re able to do because of the internet. Now you have the artificial intelligence, the handwriting, character recognition, and then you have innovations that we’re doing with the crowdsourcing. And all of a sudden, you’re able to take those tasks that we’re all human, I guess bounded by human capabilities, and you’re now allowing the computer to do what the computer can do.

With the 1950 census, we are actually indexing or reviewing this automated index for every single field that was captured in the 1950 census. It’s way more data than we were dealing with for the 1940 census. Because of the cost and the time, we just wanted to make sure that we just had the most logically relevant fields captured, so occupation, and some of those fields were seen as extra fields. But for 1950, we recognize that we can do a lot more in terms of the experiences that we can provide and that these other entities can provide if we have a full index, so that’s one of the big innovations. It’s going really well.

When will the 1950 census index be complete?

(10:08)

We have a goal to get it all done by Flag Day, so that’s June 14. That will be about two months from when we really got the project going and up to speed. That just depends on how many people come and participate.

There’s more than one way to participate. We feel like we have a lot of options, and it’s more accessible than it’s ever been because of how recent (the 1950 census) is. Recognizing handwriting from 1950s is not that different from recognizing handwriting from a week ago. Things haven’t changed that dramatically. And so, it’s a really accessible experience. And these are people that everybody knows. It’s kind of fun to come in and see what you can find in those areas where your family is from.

Innovations in the 1950 Census Index

(11:07)

Lisa: Exactly. You said something which I hope everybody really appreciates, which is that you indexing every field. I mean, you must have gotten excited when you heard that was really going to be possible. It’s a game changer because now you can slice and dice data in so many ways. You can look up everybody who worked on the railroad or whatever the fields are that were filled out. What do you think the impact will be of that? Will that change anything about genealogy research?

Jim: Yes, it will. And not just genealogical research but also understanding the makeup of our country in 1950. And really understanding the history of our nation because that is part of your family history is enabled by capturing those additional fields. Being able to see differences in income, differences in occupation from region to region, being able to easily see, neighborhoods.

The address for the 1950 census is similar to the 1940 census in that it’s a vertical capture down the side of the forms. So that is something that just allows people to see what’s there today, if their house is still there. These are experiences that that we’ve dreamed of but without the index it is impossible to provide that sort of an experience. And so now with the commercial entities and what we’re trying to do, you’re going to have a lot of different experiences now that are unlocked and available because of these innovations. And especially with Ancestry’s (technology) it has enabled us to do this.

Is the 1950 census available for free?

(13:06)

Lisa: Since you’re partnering together, is it available at Ancestry for free as well as for FamilySearch?

Jim: Ancestry will make their own businesses decisions. But yes, initially, it’ll be available for free. They’ve opened up the 1940 census recently, and that’s been available for free. I don’t know what all their future plans are. It allows them a lot of flexibility on how to do that. Of course, we make everything we can available for free at FamilySearch.

Again, there’s going to be a lot of different experiences that are available around this record set. So, it’s exciting going all the way back to how the National Archives made it available. It’s really democratizing the records. I think their goal is to just make it accessible to as many people as possible. And then it’s these other organizations that have a vision for what they can do with those records.

Lisa: Yes, and you guys certainly had the vision around the indexing project. That’s something that is such a skill that you’ve all developed and really fine-tuned. You’ve been able to crowdsource so much of what then becomes available to everybody.

Tell folks how they can get involved in it. And I’m really interested in some of the changes. I was very excited to hear that people will be able to have, in a way a more personal indexing experience. Tell folks about that.

Jim: Something that everybody wants to do when they come in and volunteer and get involved in a project is to find their own family. That will be expedited. When the index is published and available, after it’s been reviewed, everybody’s going to have that wonderful experience. But even on the review side, we’ve made it so people can search for a specific location down to the county level, or, in some cases down to the city level. Then you can actually search for a surname, or last name within that location. Now, if your family hasn’t already been reviewed, you’ll be able to review it if it hasn’t been reviewed. That just means that it’s going to be published sooner, because progress has already been made. And then you can come back and review it.

How to make corrections to the 1950 census index

(15:42) If for some reason, the person who reviewed it did it wrong, you can still make corrections. We do corrections on FamilySearch. Ancestry does corrections on Ancestry. And we are sharing whatever corrections are made on FamilySearch with Ancestry so they can get the benefit of any corrections that are made on our website as well. So that’s terrific.

For the 1940 census we had 163,000 people come and help and get involved. And with how easy it is for 1950, we think that we’ll have well over 200,000 people who will come and want to review these names.

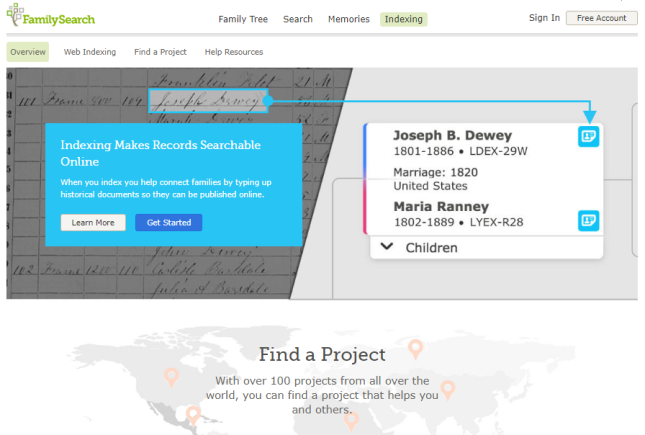

How to volunteer to index the 1950 census

(16:30) If you want to get involved, there are a couple different places you can go. But the easiest place to remember is familysearch.org/1950census. And on that page, there’s a lot of information. Near the top of the page there’s a big link to join the project and to come over and participate.

The project is ongoing. All the states are there, some have already been published. Come and get involved and see what you can do. It’s going very quickly, and people are really enjoying it. We’re glad that it’s along as quickly as it is.

Lisa: Volunteers can do this from home from their computer. Is there a certain minimum commitment that they have to make or a certain minimum amount of technological ability?

Jim: No. This is again one of the things that’s kind of fun. I mentioned that briefly before there’s actually more than one experience or a way to participate.

Household Review

(17:42) The standard way that most people who’ve done it before want to participate is what we call the Household Review. With the household review we try to identify from the head of the house, all the members of the household or the family to the next head of the house. That can sometimes cross pages on the census forms. That is an every field review. You can review as many of those fields as you want. And then the next person can come and pick up where you left off. So that’s really fun. It does require you to be on a computer.

Name Review

(18:27) There are two other types of tasks. One doesn’t require you to be on a computer. You can be on your handheld device, your smartphone. It is what we call Name Review. So, instead of reviewing all of the fields, you can download our app called Get involved. FamilySearch Get Involved is available on the iTunes Store or the Apple Store, as well as from Google, the Android store. You can download the app and you can just start looking at the images where we have the names of the people in the census. Then you can compare that with what the computer thinks it is. You can either say yes, that’s right or no, and you can actually enhance or fix what the name is. You can do hundreds of these in an hour. I’ve done it, and it’s a fun activity. It’s really engaging if you like seeing that you’re making a difference in terms of volume. It’s a really fun way to participate.

Again, the computer doesn’t always get it right. So, you have to be really careful in the review process. But it’s super easy to just look at the image and look at the index value for the name and just make sure it’s right. You don’t have to have the app though.

Header Review

(20:00) So, there’s the Household Review or the Name Review. And then the other task is the Header Review.

every census image, every census ledger, has a header that includes all of the location information and the information about the enumeration itself. And reviewing that is a separate task. We broke that one out because again, the data is formatted differently. If you want to go in and help us, those have to be done as well to be able to publish the dataset. We invite you to come in and see what states still have the header review available, and you can help us finish out that as well. It’s not as exciting because it doesn’t include the names of the people. But it still has to be done to be able to publish the reviewed index.

Lisa: I hadn’t thought about the header, but that’s pretty important. If that’s not right, then we get way off track pretty quickly. It includes our enumeration district number, the county, etc. That makes a lot of sense.

Well, Jim, it sounds like you guys have really been innovating over at FamilySearch. We’re grateful. We’re grateful that you’re giving everybody watching an opportunity to also give back a little bit and we can all pull together and get this done by Flag Day.

Volunteer to help index the 1950 US census at familysearch.org/ 1950 census.

Thank you so much. And I sure hope we’ll talk again even before the 1960 census!

Jim: I hope so! Thank you, Lisa. It’s been a pleasure to be with you today.

Resources

Downloadable ad-free Show Notes handout for Premium Members.

Learn more about becoming a Genealogy Gems Premium Member.

Recently,

Recently,

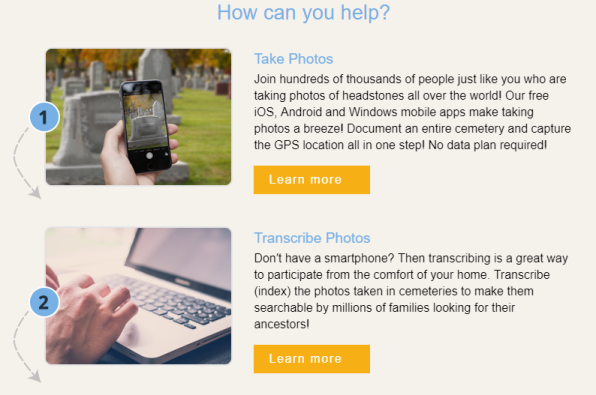

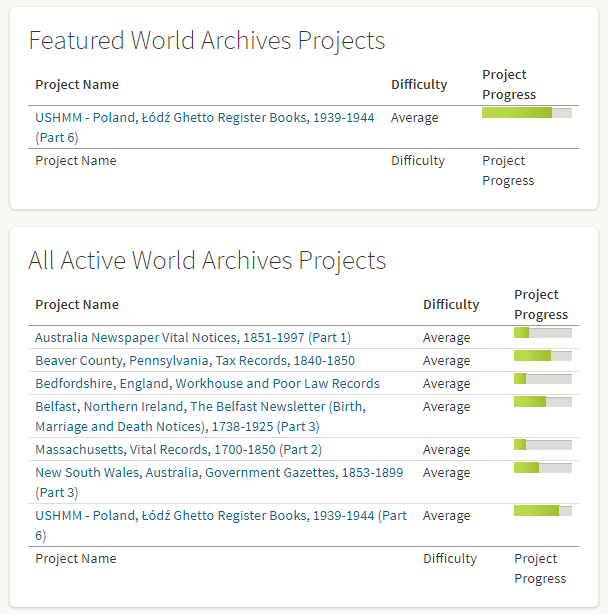

Click on one of the opportunities above–or tell us about one you’ve tried–to give back to your genealogy community this season. This largely-invisible community is all around us and enriches all our efforts, from late-night research sessions by ourselves (in records indexed by volunteers!) to local societies who host classes that inspire us or who answer our obituary inquiries and Facebook posts about their locales. If you are already one of those volunteers, THANK YOU. You are a gem and we here at Genealogy Gems are grateful for you.

Click on one of the opportunities above–or tell us about one you’ve tried–to give back to your genealogy community this season. This largely-invisible community is all around us and enriches all our efforts, from late-night research sessions by ourselves (in records indexed by volunteers!) to local societies who host classes that inspire us or who answer our obituary inquiries and Facebook posts about their locales. If you are already one of those volunteers, THANK YOU. You are a gem and we here at Genealogy Gems are grateful for you.