by Lisa Cooke | Dec 3, 2013 | 01 What's New, British, Church, FamilySearch

Over a million Church of England records from the county of Norfolk are among materials now indexed at FamilySearch.org.

Happisburgh church of St. Mary’s, Norfolk. Image by Martin at Flickr Creative Commons.

The collection includes bishops’ registers of baptisms, marriages and burials from the mid-1600s to the mid-1900s.

- Baptismal records may include the child’s name, date and place of baptism, parents’ names and residence, legitimacy status of the child, father’s occupation and minister’s name.

- Marriage records may include the names, ages, marital status and residence of bride and groom; date and place of marriage; fathers of the bride and groom and information on whether banns were published.

- Burial records may include the name, age, and residence of the deceased and the date and parish of burial.

The Church of England was a state-sponsored church. This helps genealogists because it means that most everyone who lived there (until the mid-1800s or so) is likely to show up in Church of England records. So if you had English ancestors who lived in Norfolk, take a look. These images have been online since 2010, but the new index makes them a lot easier to search!

by Lisa Cooke | Nov 1, 2017 | 01 What's New, Heirloom, History, Memory Lane |

Flour sack dresses show how resourceful housewives of the past “made do” with whatever was at hand. But they weren’t the only clever ones–see how savvy flour and feed companies responded to their customers’ desires for cuter sacking.

The History of Flour Sack Dresses

During the tough economic times of the Great Depression, housewives needed new ways to produce what their families needed, including clothing. So they looked around the house–and even the barn–for extra fabric they could turn into dresses, aprons, or shirts.

Female workers pose with sacks of flour in the grounds of a British mill during WWI. 1914. By Nicholls Horace [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. (Click to view.)

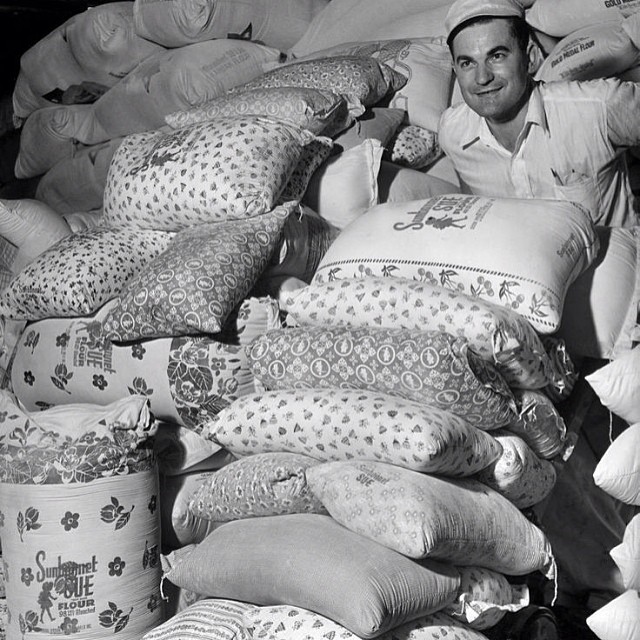

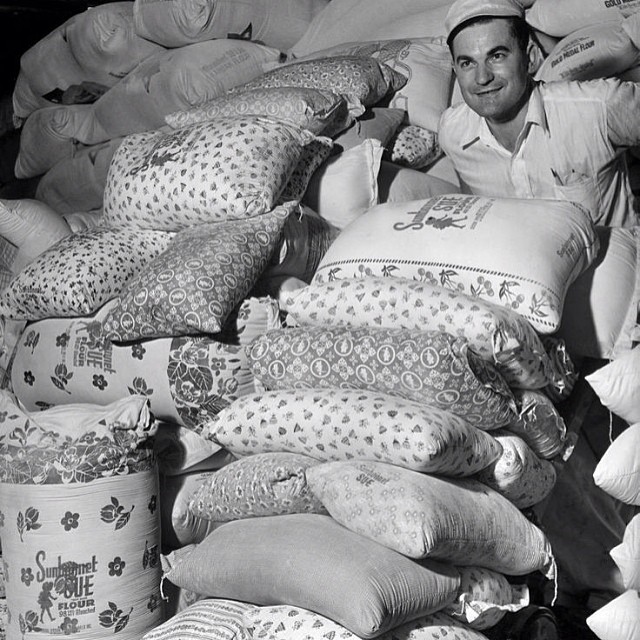

By the 1920s, these sacks had gotten a little cuter, some with gingham checked or striped patterns. So frugal housewives of the 1930s turned feed and flour sacks into everyday clothing for themselves and their families.

It didn’t take long for manufacturers of flour and feed to start printing their sacks with colors and patterns that women would want to buy. Some put patterns for dolls or stuffed animals on the bags. They even made it so you could wash out the ink so your new dress wouldn’t be a walking ad for Sunbonnet Sue flour! Newspapers and publishers also began printing patterns and ideas for getting the most out of the small yardage of a flour or feed sack.

Old photo of printed fabric flour sacks or ‘feedsacks’. Flickr Creative Commons photo, uploaded by gina pina. Click to view.

A fascinating article at OldPhotoArchive.com shows some great images of flour and feed sack dresses. And the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History has an online article about a feed sack dress from 1959, because these didn’t go out of fashion when the Great Depression ended! According to that article, World War II caused a cotton fabric shortage. Feed and flour sack dresses again became popular.

After the war, women continued to make these dresses, encouraged even further by national sewing contests. Women even sold off their extra flour or feed sacks to others who wanted them.

Memories of Flour Sack Dresses

A woman named Denise posted a neat memory at the end of the Smithsonian article. She says:

Click to view my Facebook post about my grandma’s 1940s house dresses.

“I was born in 1951. For the first four-five years of my life, all my dresses were sewn by my paternal grandmother from feed sacks. She would layer the fabric two to three layers deep and cut the main dresses from the same pattern. She would then add different details to each dress. Some sleeveless, some with little puffy fifties sleeves, some with self collars, some with contrasting solid collars. We lived in rural north GA, but nonetheless I was teased by my parents’ friends about my feed-sack dresses. Oh how I longed for store-bought dresses. Now, oh how I long to have some of those wonderful little feed sack dresses! They weren’t thought of as precious at all, so no one ever thought to keep them!”

I think a lot of people have fond—or at least vivid—memories of old dresses like these. I do! I posted a photo of my grandma’s old house dresses from the 1930s and 1940s on Instagram. What a response from everyone there and on Facebook! My grandma’s house dresses weren’t made from flour sacks, but they’re from the same era.

Want to see some eye-candy vintage fabrics or date your own family heirloom clothing? Check out these books:

Care for Your Flour Sack Dresses or Other Heirlooms

Take better care of your own family heirloom pieces, whether they are photos, vintage fabrics, documents or other objects. Get Denise Levenick’s popular book How to Archive Family Keepsakes: Learn How to Preserve Family Photos, Memorabilia and Genealogy Records. This book will help you sort, identify, and preserve your own treasured family artifacts and memorabilia.

Take better care of your own family heirloom pieces, whether they are photos, vintage fabrics, documents or other objects. Get Denise Levenick’s popular book How to Archive Family Keepsakes: Learn How to Preserve Family Photos, Memorabilia and Genealogy Records. This book will help you sort, identify, and preserve your own treasured family artifacts and memorabilia.

Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links and Genealogy Gems will be compensated if you make a purchase after clicking on these links (at no additional cost to you). Thank you for supporting Genealogy Gems!

by Lisa Cooke | Apr 23, 2015 | 01 What's New, 1950, Brick Wall, Research Skills

When we try to research our family history from recent decades, we often find privacy barriers: U.S. census records for 1950 and beyond

1950s Fords by Bob P.B. on Flickr Creative Commons. Some rights reserved.

are closed, as are many vital records. Here are some ideas for finding family history in the 1950s and beyond:

1. Interview relatives. The good news is that in many families, there are relatives around who remembers the 1950s. If there’s not, then look to the memories of the next living generation.

Interviewing a relative is one of the most fun and meaningful ways to learn your family history. You can ask specific and personal questions, deepen your relationships with those you interview and gain a better understanding of the lives that led to you. Older people often love to have someone take a sincere interest in them. The free Family History Made Easy podcast episode 2 has a great segment on interviewing your relatives.

2. Read the newspaper. Use newspapers to find obituaries and discover more about daily life, current events, popular opinions of the time, prices for everyday items and more. It’s getting easier than ever to find and search digitized newspapers online, but more recent papers may still be under copyright protection.

Use online resources like to discover what newspapers served your family’s neighborhood, or even whether an ethnic, labor or religious press would have mentioned them. In the US, I always start with the US Newspaper Directory at Chronicling America to search for ALL newspapers published in a particular place and time, as well as the names of libraries or archives that have copies of these papers. Historical societies and local public libraries are also wonderful places to look for newspapers. My book, How to Find Your Family History in Newspapers, teaches readers what to look for in papers and how to locate them online and offline.

3. Search city directories. By the 1950s, most towns and cities published directories of residents, mostly with telephone numbers. I use annual directory listings to track buy generic medication online families from year to year. These might give you your first clue that someone moved, married, separated, divorced or died! I can often find their exact street address (great for mapping!), who lived at the house and sometimes additional information like where they worked, what their job was or who they worked for.

Ancestry.com has over a billion U.S. city directory entries online, up to 1989. But most other online city directory collections aren’t so recent. Look for city directories first in hometown public libraries. Check with larger regional or state libraries and major genealogical libraries.

4. Search for historical video footage. YouTube isn’t just for viral cat videos. Look there for old newsreels, people’s home movies and other vintage footage. It’s not unusual to find films showing the old family neighborhood, a school or community function, or other footage that might be relevant to your relatives.

Use the YouTube search box like you would the regular Google search box. Enter terms like “history,” “old,” “footage,” or “film” along with the names, places or events you hope to find. For example, the name of a parade your relative marched in, a team he played on, a company she worked for, a street he lived on and the like. It’s hit and miss, for sure, but sometimes you can find something very special.

My Contributing Editor Sunny Morton tried this tip. Almost immediately, with a search on the name of her husband’s ancestral hometown and the word “history,” she found a 1937 newsreel with her husband’s great-grandfather driving his fire truck with his celebrity dog! She recognized him from old photos and had read about his dog in the newspapers. (Click here to read her stunned post.) Learn more about searching for old videos in my all-new second edition of The Genealogist’s Google Toolbox, which has a totally updated chapter on YouTube.

Click here to read more about the 1950s U.S. census: when it will be out and how you can work around its privacy restrictions.

by Lisa Cooke | Feb 13, 2019 | 01 What's New, Military |

Our Military Minutes Man Michael Strauss revisits the first subject he covered with us on the Genealogy Gems Podcast: Draft Registrations for both World War I and World War II. Since that first segment aired several listeners have had questions and sent in comments...

Feedsack Secrets: Fashion from Hard Times

Feedsack Secrets: Fashion from Hard Times