by Lisa Cooke | Feb 12, 2018 | 01 What's New, German |

For a long time, German census records were thought not to exist. But they do! A leading German genealogy expert tells us how they’ve been discovered and catalogued—and where you can learn about German census records that may mention your family.

Thanks to James M. Beidler for contributing this guest article. Read more below about him and the free classes he’ll be teaching in the Genealogy Gems booth at RootsTech 2018 in a few short weeks.

German census records DO exist

One of the truisms of researching ancestors in America is that the U.S. Census is a set of records that virtually every genealogist needs to use.

From its once-a-decade regularity to its easy accessibility, and the high percentage of survival to the present day, the U.S. Census helps researchers put together family groups across the centuries.

On the other hand, the thing that’s most distinctive about German census records is that for many years they were thought not to even exist.

For Exhibit A, look at this quote from a book published just a few years ago: “Most of the censuses that were taken have survived in purely statistical form, often with little information about individuals. There are relatively few censuses that are useful to genealogists.”

The book from which the above statement was taken is The Family Tree German Genealogy Guide. And the author of that book is … uh, well … me!

In my defense, this had been said by many specialists in German genealogy. The roots of this statement came from the honest assessment that Germany, which was a constellation of small states until the late 1700s and not a unified nation until 1871 when the Second German Empire was inaugurated, had few truly national records as a result of this history of disunity.

As with many situations in genealogy, we all can be victims of our own assumptions. The assumption here was that because it sounded right that Germany’s fractured, nonlinear history had produced so few other national records, those census records didn’t exist.

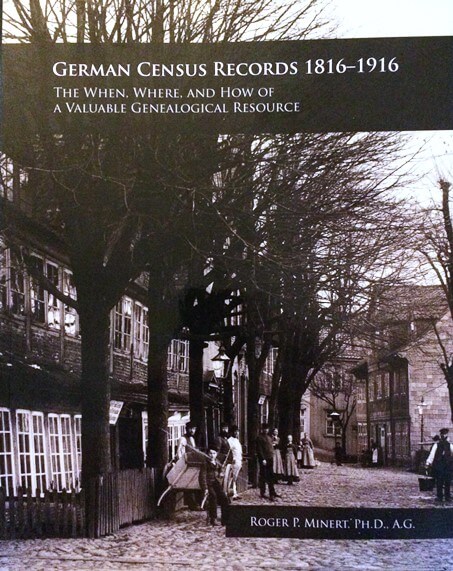

A few census records from northern German states (see below) had been microfilmed by the Family History Library, but for all intents and purposes, a greater understanding of the “lost” German census records had to wait for a project spearheaded by Roger P. Minert, the Brigham Young University professor who is one of the German genealogy world’s true scholars.

Finding lost and scattered German census records

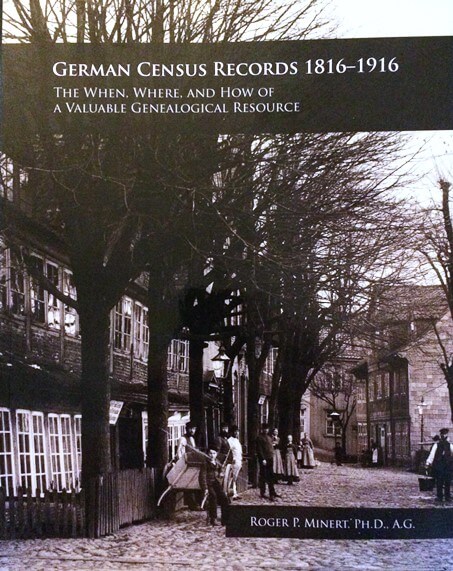

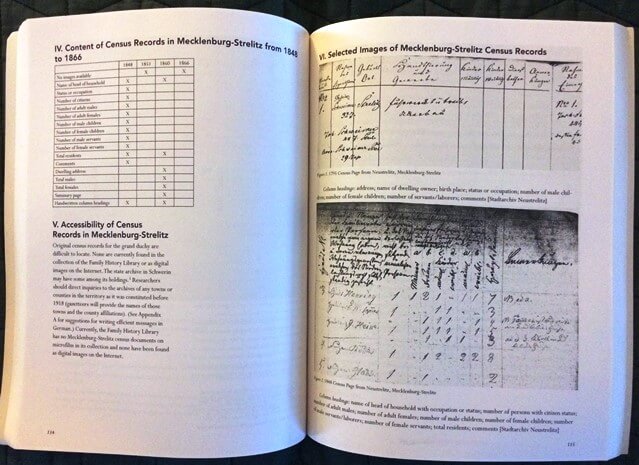

It can be said that Brigham Young University professor Roger Minert “wrote the book” on the German census. That’s because he literally did: German Census Records, 1816-1916: The When, Where, and How of a Valuable Genealogical Resource. A sample page is shown below.

Minert had a team help him get the project rolling by writing to archivists in Germany before he took a six-month sabbatical in Europe. During this time, he scoured repositories for samples of their German census holdings (To some extent, Minert’s project had echoes of an earlier work led by Raymond S. Wright III that produced Ancestors in German Archives: A Guide to Family History Sources).

What resulted from Minert’s project was the census book and a wealth of previously unknown information about German censuses.

While a few censuses date to the 18th century in the German states (some are called Burgerbücher, German for “citizen books”), Minert found that the initiation of customs unions during the German Confederation period beginning after Napoleon in 1815 was when many areas of Germany began censuses.

The customs unions (the German word is Zollverein) needed a fair way to distribute income and expenses among member states, and population was that way. But to distribute by population, a census was needed to keep count, and most every German state began to take a census by 1834.

Until 1867, the type of information collected from one German state to another varied considerably. Many named just the head of the household, while others provided everyone’s names. Some include information about religion, occupation and homeownership.

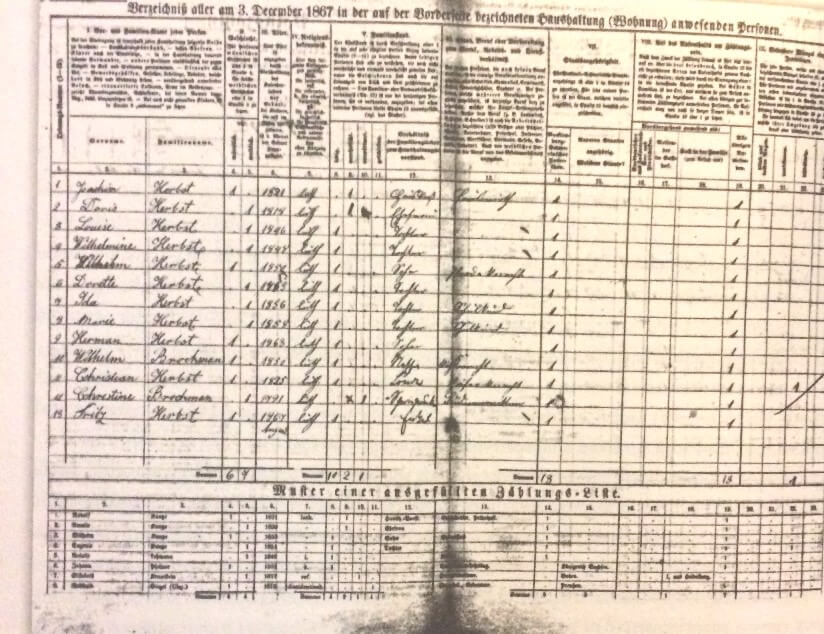

The year 1867 was a teeter-totter point Minert calls it “for all practical purposes the first national census.” Prussia—by then the dominant German state and whose king would become the emperor just a few years hence—spearheaded the census effort.

After the founding of the Second German Empire, a census was taken every five years (1875 – 1916, the last census being delayed by World War I). While there was some variance in data from one census to another, they all included the following data points:

- names of each individual,

- gender,

- birth (year and, later, specific dates),

- marital status,

- religion,

- occupation,

- citizenship,

- and permanent place of residence (if different from where they were found in the census).

While some of these censuses are found in regional archives within today’s German states, in many cases the census rolls were kept locally and only statistics were forwarded to more central locations.

Interestingly, there has been a lack of awareness even among German archivists that their repositories have these types of records! Minert says in his book that in three incidences, archivists told him their holdings included no census records, only to be proved wrong in short order.

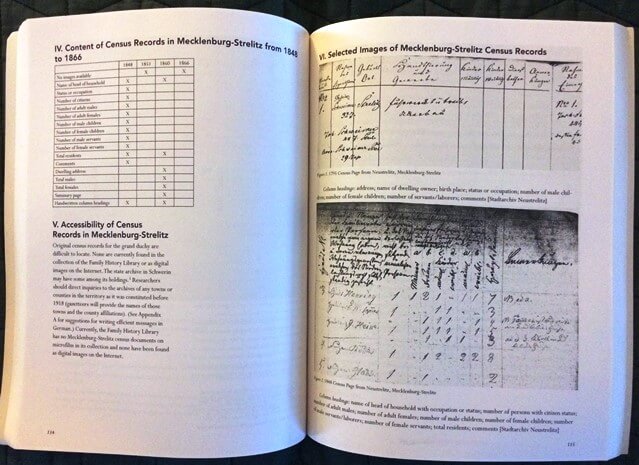

Minert’s book goes through the old German Empire state by state and analyzes where researchers are likely to find censuses. For each state, there is also a chart on the pre-Empire censuses and what information they included.

Researchers wishing to access these records will often need to contact local archives. If you’ve uncovered a village of origin for an immigrant, you could contact them directly by searching for a website for the town, then emailing to ask (politely but firmly) whether the archives has census records.

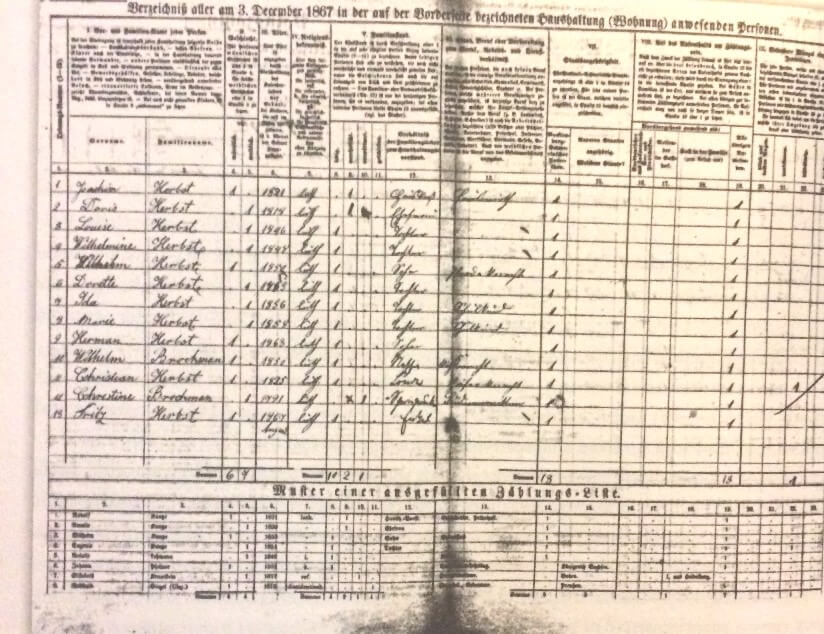

FamilySearch has placed online German census records for Mecklenburg-Schwerin (1867, 1890 and 1900; the one shown below is from 1867).

The Danish National Archives has some census records online for Schleswig-Holstein (much of the area was Danish until they lost a war with Prussia in 1864).

Other Census-Like Lists

In addition to these censuses, many areas of Germany have survivals of tax lists that serve as a record substitute with some data points that are similar to censuses. The lists generally show the name of the taxpayer and the amount of tax paid.

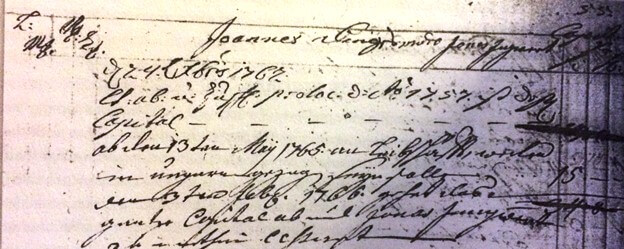

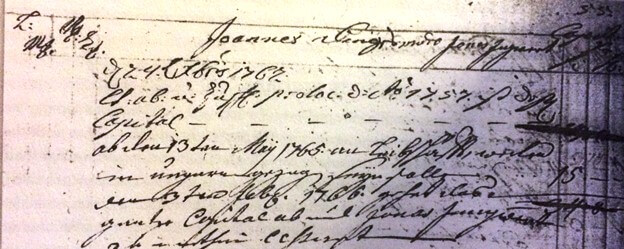

In some cases, versions of the lists that include the basis for the tax (usually the value of an interest in real or personal property) have survived. The lists may also include notes about emigration. Here’s a sample tax record from Steinwenden Pfalz.

Some of these tax lists are available in the Family History Library system.

The best “clearinghouse” that reports the holdings of various repositories in Germany is Wright’s Ancestors in German Archives. As with the census records, the best way to contact local archives directly would be to search for a website for the town. E-mail to ask whether such lists are kept in a local archive.

In my personal research, tax records have proved crucial. For example, they confirmed the emigration of my ancestor Johannes Dinius in the Palatine town of Steinwenden. These records showed the family had left the area a few months before Dinius’ 1765 arrival in America.

James M Beidler is the author of The Family Tree German Genealogy Guide and Trace Your German Roots Online.

Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links and Genealogy Gems will be compensated if you make a purchase after clicking on these links (at no additional cost to you). Thank you for supporting Genealogy Gems

by Lisa Cooke | Nov 29, 2017 | 01 What's New, Ancestry, DNA

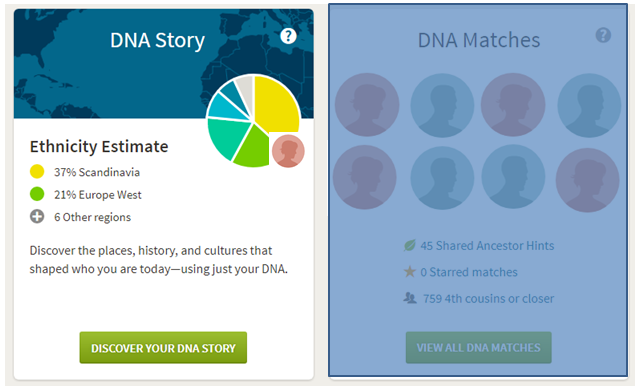

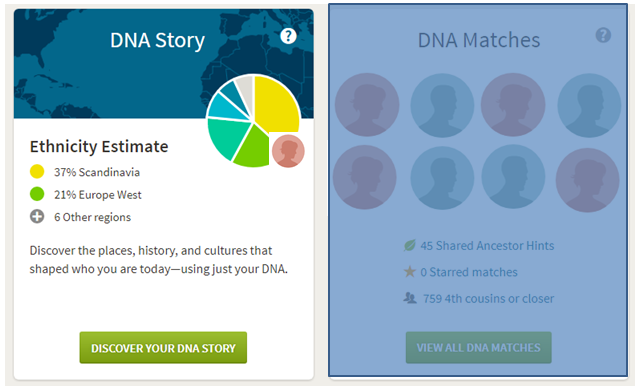

A new AncestryDNA opt-out option allows DNA test takers to not participate in DNA match lists: they do not receive matches or show up in others’ match lists. Your DNA Guide Diahan Southard weighs on in the implications for genealogy researchers who may worry about cousin matches they may miss.

New AncestryDNA Opt-Out Policy

Ancestry.com recently announced an update to their privacy policy. Current and future AncestryDNA users now have the option to opt out of the DNA matching feature.

Ancestry.com recently announced an update to their privacy policy. Current and future AncestryDNA users now have the option to opt out of the DNA matching feature.

When you take a DNA test, you receive two different kinds of results from the DNA sample that you submit to your testing company:

- information about your ancestral origins and

- a list of your DNA cousins.

Opting out of matching essentially cuts the value of this product in half. You only get the ancestral origin information, and you forfeit access to your list of genetic matches. Opting out doesn’t just mean you can’t see them: it means that they can’t see you either.

AncestryDNA joins 23andMe in providing this option to their clients. You can look at this move as Ancestry’s response to an ever-expanding global audience, many of whom are not genealogists or are reluctant to have their DNA compared to others for a variety of reasons. It is important for them as a company to provide options for their clients to experience their product in a way that works best for them.

What the AncestryDNA Opt-Out Policy May Mean for You

What does this new opt-out option mean for genealogists? Hopefully, not much will change. Ancestry reports that overwhelmingly, people are opting in.

What does this new opt-out option mean for genealogists? Hopefully, not much will change. Ancestry reports that overwhelmingly, people are opting in.

There has been quite a bit of push-back to this announcement, especially from the adoption community. DNA testing has been a tremendous source of information for those seeking out their biological relatives, and many fear that this change will limit access to quality DNA matches. But we will all still be able to do good genetic genealogy work, even as we are each allowed to choose whether to participate in the matching feature. To understand this better, it is important to see this issue from the other side, from the side of a person who might want to opt out. Here are two possible scenarios:

Scenario #1: Susan would really like to explore her heritage. She hasn’t tested before because she didn’t want to see cousin matches for a variety of personal reasons. But now she does test and opts-out. The community hasn’t lost anything because Susan would never have tested in the first place. But after exploring her ethnicity results and noticing membership in a couple of Genetic Communities, she begins to wonder more about her ancestors and decides to opt-in to matching, after all. In this scenario, the Opt-Out policy offers users a way to comfortably give DNA testing a try.

Scenario #2: Ryan heard about AncestryDNA while watching TV last year and ordered a kit. But then last week he heard about the ability to opt out, and went in and changed his account settings. So one day you could see Ryan on your match list, and the next you didn’t. We as a community would certainly see that as a loss. However, consider the circumstances that might have caused Ryan to hit that opt-out button. Perhaps Ryan had no idea how to use the match list, no interest in using it, and found it a bother to get correspondence from people. Perhaps Ryan found something unexpected, like that he wasn’t his father’s child, and he needed some time to deal with it. Maybe Ryan is under pressure from his sister, who didn’t want him to test in the first place (perhaps she knows something he doesn’t about their family tree, or she’s afraid of how any results and revelations might impact her). The short of it is: It doesn’t matter why Ryan opted out, it is his personal right to do so. Just as an adoptee has the right to seek out their heritage, others have the right to keep their family secrets to themselves. This scenario does support the idea that you should review your DNA matches frequently and record information about them in your own master match list, which I talk about in my quick reference guides, Organizing Your DNA Matches and Breaking Down Brick Walls with DNA. By promptly recording matching results, you will have them to work with even if the tester decides later on down the road to opt out.

As a genealogy community, we can educate others about the value of the match list, while at the same time cautioning them that unexpected connections may appear. So in everyday conversations, share your own experiences—whatever these may be. Maybe it was affirming for you to see that the dad you grew up knowing is indeed your biological father. Perhaps you can share a story about the power of using a list of fourth cousins to discover information about your third-great-grandfather. Maybe you’ve discovered a new connection—and maybe that connection isn’t yet comfortable or fully explained, but you’re glad to know about it.

Learn More about AncestryDNA Testing

Get the most out of your AncestryDNA testing experience with my quick reference guides! I recommend:

- A Guide to AncestryDNA How to find your best DNA matches, interpret ethnicity results, link your tree, understand relationship ranges and DNA Circles, and work with Shaky Leaf hints.

- Autosomal DNA for the Genealogist. What autosomal test can tell you, who can be tested, how to interpret your ethnicity results, and more.

- Organizing Your DNA Matches. How to keep track of your matches and apply what you learn from them to your family history.

- Breaking Down Brick Walls with DNA. What to do next to maximize the power of DNA testing in genealogy. Take your DNA testing experience to the next level and make new discoveries about your ancestors and heritage!

Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links and Genealogy Gems will be compensated if you make a purchase after clicking on these links (at no additional cost to you). Thank you for supporting Genealogy Gems!

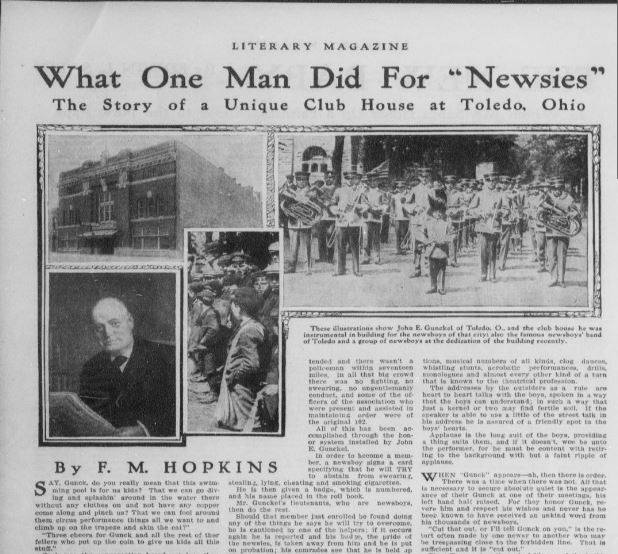

by Lisa Cooke | Nov 6, 2013 | 01 What's New, History, Newspaper

Newsboys or “newsies” used to sell the news. But for a time in American history, they were the news!

Newsboy. Little Fattie. Less than 40 inches high, 6 years old. Been at it one year. May 9th, 1910. Location: St. Louis, Missouri. Wikimedia Commons image, original at Library of Congress.

You’d know them by their common call: “Read all about it!” It was their job to sell stacks of inexpensive newspapers on every street corner that would support them. The Library of Congress has posted a fascinating page about the history of newsies, including their own appearance in the papers.

In 1899, newspaper prices rose–and that cut into the profit margins of boys who had very little profit to begin with. In New York City, many newsboys refused to sell papers published by Pulitzer and Hearst. Over the next few years, the newsboys didn’t exactly unionize, but they did organize. Eventually they formed the National Newsboys’ Association, which evolved into today’s Boys Club and Girls Club.

It’s interesting to read how the newspapers reported the doings of the boys who were essentially their salespeople. I bet it was a tricky place to be caught: a newspaper couldn’t afford to totally alienate their own best salesmen. Those salesmen were actually children, whom nobody wants to be accused of targeting. But their activities were aimed at driving down prices. In some cases, you see newspapers taking “the high road” and reporting charitable efforts to help these boys, like this story from the 1909 Washington Herald:

Click here to read this full story on Chronicling America. And click here to “read all about” newsboys and their role in American newspaper life.

Remember, stories like these are the kind that shaped our ancestors’ lives. Whether we find our relatives mentioned directly in the paper or we just see what life was like around them, we can learn so much from reading the same newspapers they did. Learn more from my book How to Find Your Family History in Newspapers–and Genealogy Gems Premium Subscribers can check out “Getting the Scoop on Your Ancestors in Newspapers” in the Premium Videos section.

by Lisa Cooke | Dec 2, 2013 | 01 What's New, Conferences

The program for the 2014 National Genealogical Society Conference has been released! The lineup for the Richmond, Virginia event looks fantastic. Here’s the official summary:

“Conference highlights include a choice of more than 175 lectures, given by many nationally known speakers and subject matter experts about a broad array of topics including records for Virginia and its neighboring states; migration into and out of the region; military records; state and federal records; ethnic groups including African Americans, German, Irish, and Ulster Scots; methodology; analysis and problem solving; and the use of technology including genetics, mobile devices, and apps useful in genealogical research.”

I’ll be at NGS 2014 teaching these classes:

- Google Search Strategies for Common Surnames

- Tech Tools that Catapult the Newspaper Research Process into the 20th Century

- Find Living Relatives Like a Private Eye

Looking for my classes? Open the registration brochure (link below) and hit Ctrl+F, then type my last name and hit enter. Hit the up and down arrows to browse the places where my name appears.

Registration opens on December 1, just after Thanksgiving weekend in the U.S.

Why read over the program now? Because like early holiday shoppers, you’ll get the best selection if you’re ready to go when it opens. A number of special events (see the brochure) have limited seating so you’ll want to register as early as possible to ensure your seat. The 16-page downloadable registration brochure addresses logistics as well as the program.

Read more about it on the NGS website, or jump to these helpful URLS:

Guide for 1st-time NGS attendees

Up-to-date hotel info

Conference blog

Ancestry.com

Ancestry.com