Polish Genealogy: 4 Steps to Find Your Family History

Researching your Polish genealogy may seem a little intimidating at the start. Read these get-started tips from a Polish genealogy veteran at Legacy Tree Genealogists. Then you’ll know how to dive right into your Polish family history–and where to turn if you need a little help.

Thanks to Legacy Tree Genealogists for supplying this guest blog post. Legacy Tree employs researchers with a wide range of expertise. They asked their Polish expert, Julie, to share tips for finding Polish ancestors, based on her decades of experience.

If you’re an American researching your Polish ancestors, you aren’t alone. Polish Americans make up the largest Slavic ethnic group in the United States, second largest Central and Eastern European group, and the eighth largest immigrant group overall. So how do you begin tracing your roots in Poland?

Get Started: 4 Polish Genealogy Tips

1. Get to know the basics of Polish history.

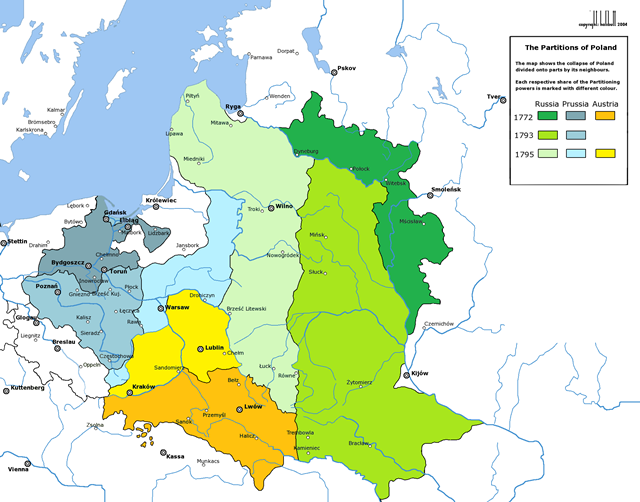

Probably every Polish-American family has heard mention of the “border changes” that were supposedly the reason why Grandpa’s papers say he was from Austria, although everyone knew he was Polish. What many people don’t realize is that Poland did not exist as an independent nation from 1795 until 1918. Historically, Polish lands were partitioned among the Russian, Prussian, and Austrian Empires, and ethnic Poles were citizens of one of those three nations. This is why you might see your Polish ancestors stating Russian birth on the 1910 U.S. census, but Polish birth on the 1920 U.S. census, after Poland was reestablished as an independent nation.

By Rzeczpospolita_Rozbiory_3.png: Halibuttderivative work: Sneecs (talk) – Rzeczpospolita_Rozbiory_3.png, CC BY-SA 3.0, click to view on Wikipedia.

2. Determine your Polish ancestor’s religion.

Buffalo, New York. Children of the Polish community leaving church with baskets of food on the day before Easter. Library of Congress photo; digital image via Wikipedia. Click to view.

Although we in the U.S. are accustomed to the separation of church and state, this was not the case in many places. In Poland, it was common for priests, ministers, or rabbis to act as civil registrars, blending ecclesiastical and government authority as they recorded births, marriages, and burials. Although this was the protocol in all three partitions for the majority of the 19th century, the exact span of dates in which this was true vary based on the partition in which your ancestors lived, and greatly affects where you should be searching for the records you need. In “Russian Poland,” for example, civil record keeping began in 1808 with Roman Catholic priests acting as civil registrars for people of all faiths (not just Catholics). Beginning in 1826, each faith was allowed to keep its own civil records using a paragraph-style format that remained relatively stable through the 1930s. Civil registration that was independent of any religious organization did not begin until 1945.

The fact that civil copies of church records were made increases the likelihood that records survived for your ancestor’s town. There’s a persistent myth that “all the records were destroyed in the wars,” but that’s simply not true in most instances. Existing records for some locations date back to the 1600s, but in other places surviving records are sparser.

3. Use U.S. records to determine your ancestor’s precise place of origin.

Grandma may have said that her father came from Warsaw, but most of our ancestors came from small villages, not large cities. It’s more likely that her father was using Warsaw as a point of geographic reference to give people a rough idea of where he lived, since others are unlikely to recognize the name of a small village. This means that you most likely won’t find his birth record by looking for it in Warsaw, but it also leaves you in the dark about where to look instead.

What kinds of records are most likely to indicate a precise place of birth? Passenger manifests and petitions for naturalization (if dated after 1906) are great sources for this information. If your Polish ancestors were Catholic, church records from the parish they attended in the U.S. are much more likely to contain specific place of birth than their civil equivalents. These include marriage records for immigrants who married in the U.S., baptismal records for U.S.-born children of immigrants, and church death/burial records.

What kinds of records are most likely to indicate a precise place of birth? Passenger manifests and petitions for naturalization (if dated after 1906) are great sources for this information. If your Polish ancestors were Catholic, church records from the parish they attended in the U.S. are much more likely to contain specific place of birth than their civil equivalents. These include marriage records for immigrants who married in the U.S., baptismal records for U.S.-born children of immigrants, and church death/burial records.

Click here for an article about a woman who found her Polish Catholic grandparents’ church marriage record–and with it their overseas birth place–at St. Stanislaus parish in Buffalo, NY. You’ll also learn tips for finding Catholic church records in the U.S.

If your ancestors were Jewish, check cemetery records for mention of any landsmannschaft to which they might have belonged. Landsmannschaften were fraternal aid societies organized by immigrants from the same town in Europe, and they frequently purchased large burial plots for their members.

4. Use a gazetteer to determine the parish or registry office that served your ancestor’s village.

Depending on which partition your ancestors came from, some good gazetteers include:

- The Słownik geograficzny Królestwa Polskiego i innych krajów słowiańskich, or Geographical Dictionary of the Kingdom of Poland and Other Slavic Countries, published between 1880 and 1902 in 15 volumes. The SGKP is written in Polish.

- The Skorowidz Królestwa Polskiego, which includes all of Russian Poland (officially known as the “Królestwo Polskie” or Kingdom of Poland) published in 1877. The SKP is mostly written in Polish with some text in Russian.

- Kartenmeister, an easy-to-use online gazetteer for “German Poland” that covers East Prussia, West Prussia, Brandenburg, Posen, Pomerania, and Silesia. Kartenmeister can be searched using either the German or the Polish name for a town.

- The Galician Town Locator, offered by Gesher Galicia, is another easy-to-use resource that covers the historic Galicia region, which was a part of the Austrian Empire that is now split between Poland and Ukraine.

- The JewishGen Gazetteer is a phonetic gazetteer to assist in identifying the correct location in cases where your ancestor’s place of origin is misspelled on U.S. records. It covers areas throughout Central and Eastern Europe.

Once you have correctly identified both your ancestor’s place of birth and the location of his place of worship or civil records office, you’re ready to make the jump back to records in Poland.

Get Expert Help with Your Polish Genealogy Questions

We at Legacy Tree Genealogists would be honored to assist you with any step along the way in your journey to discover your ancestral origins, including onsite research if needed. Our experts have the linguistic and research skills to efficiently find your family. Contact us today for a free consultation.

We at Legacy Tree Genealogists would be honored to assist you with any step along the way in your journey to discover your ancestral origins, including onsite research if needed. Our experts have the linguistic and research skills to efficiently find your family. Contact us today for a free consultation.

Exclusive offer for Genealogy Gems readers: Save $100 on a 20-hour research project using code GG100, valid through October 31st, 2017.

Free Scandinavian Genealogy Webinar

MyHeritage is a leading resource for Scandinavian genealogy research. Now they are offering a free webinar for those researching Danish,  Finnish, Norwegian, Swedish and Icelandic ancestry.

Finnish, Norwegian, Swedish and Icelandic ancestry.

On Wednesday, April 15, Mike Mansfield, MyHeritage Director of Content and Jason Oler, MyHeritage Senior Program Manager, will host a program packed with research tips and strategies for navigating the millions of Scandinavian genealogy records now on MyHeritage. Click here to register.

Ready to learn about Scandinavian genealogy NOW? Genealogy Gems Premium members can access Premium Podcast Episode #15, in which Lisa interviews Scandinavian research expert Ruth Mannis at the Family History Library. Ruth simplifies and clarifies the process and reassures us that everyone can have success finding their Scandinavian roots. If you’re not a Premium member yet, you’re missing out on gems like Ruth Mannis’ interview–and more than 100 more premium podcasts like these and dozens of genealogy video tutorials. Get a year’s access

to all of this for one low price. Click here to learn more.

Share World War I Family History

To commemorate the centennial of the First World War, and to mark the last full month of the exhibition Myth and Machine: The First World War in Visual Culture, the Wolfsonian at Florida International University (FIU) created a special Tumblr for sharing family stories, WWI memorabilia, and genealogy research tips called #GreatWarStories.

To commemorate the centennial of the First World War, and to mark the last full month of the exhibition Myth and Machine: The First World War in Visual Culture, the Wolfsonian at Florida International University (FIU) created a special Tumblr for sharing family stories, WWI memorabilia, and genealogy research tips called #GreatWarStories.

I first crossed paths with FIU’s Digital Outreach Strategist Jeffery K. Guin in 2009 when he interviewed me for his Voices of the Past website and show. Jeff was an early innovator in the world of online history, and he’s now brought those talents to the Wolfsonian, a museum, library and research center in Miami that uses its collection to illustrate the persuasive power of art and design.

The Wolfsonian team of historical sleuths is inviting the public at large to help them unearth the forgotten impact of the Great War by posting family facts, anecdotes, documents, and photographs. They were inspired by their current art exhibition Myth and Machine: The First World War in Visual Culture which focuses on artists’ responses to the war. They hope that #GreatWarStories project at Tumblr will be a “living, breathing digital collection of personal WWI stories, photos, documents and letters compiled in remembrance of the transformational war on the occasion of its centennial.”

Jeff asked me to join in on this buy add medication online history crowd-sourcing effort, and it was easy to comply. Several years ago in going through the last of my Grandmother’s boxes, I found a booklet she had crafted herself called The World War.As a high school student, and daughter of German immigrant parents she set about gathering and clipping images from magazines and newspapers, depicting this turning point in history. I’ve been anxious to share it in some fashion, and this was my opportunity. Here is the result:

Here are some ways you can contribute:

- Sharing the story of your family’s WWI-related history through photos, documents, or anecdotes (possibilities include guest blogging, video/podcast interview, or photo essay)

- Using your expertise and unique perspective as a launching pad for discussing the war’s impact in a different or surprising way

- Alerting the museum to related resources or materials that would dovetail with the mission of the project

To see the living, digital collection, visit http://greatwarstories.tumblr.com. If you would like to participate, send an email to greatwarstories@thewolf.fiu.edu and the Wolfsonian team will be in touch to discuss storytelling ideas.