British Isles Descendants Will Love these New Records Online

Millions of British Isles descendants—whether still living in England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales or dispersed to the United States, Canada, Australia or New Zealand, may find their ancestors in these new online records that include medieval maps, BMD and immigration...Eastern Cherokee Applications for Native American Research

Many American families have a tradition of Native American ancestry. Now, Fold3.com has made access to their Native American records collections free between November 1 and 15th. Here are the step-by-step instructions you need to know to effectively navigate the Eastern Cherokee Applications collection at Fold3.com.

Original image provided by Boston Public Library via Flickr at https://www.flickr.com/photos/24029425@N06/5755511285.

Our Purpose

Our goal is to open the doors to using all types of available genealogical records, and provide you with the skills to explore them with confidence. Our Genealogy Gems team is excited to share with you the opportunity to utilize the free access to Native American records on Fold3.com. While it can be difficult and confusing to know how to navigate these important records, this post will provide you with information to get you started and to feel a little more comfortable jumping in! Now, let’s get started.

Eastern Cherokee Applications Collection for Native American Research

The Eastern Cherokee tribe sued the United States for funds due them under the treaties of 1835, 1836, and 1845. [1] Applicants, or claimants, were asked to prove they were members of the Eastern Cherokee tribe at the time of the treaties, or descended from its members. [To learn more about the lawsuits and allocations, read “Eastern Cherokee Applications of the U.S. Court of Claims, 1906-1909,” in .pdf form provided by the National Archives and Records Administration.]

The courts ruled in favor of the Eastern Cherokees and the Secretary of the Interior was tasked to identify the persons entitled to distribution of funds. The job of compiling a roll of eligible persons was given to Guion Miller.

It is interesting to note that the funds were to be distributed to “all Eastern and Western Cherokee Indians who were alive on May 28, 1906, who could establish the fact that at the time of the treaties, they were members of the Eastern Cherokee tribe or were descendants of such persons, and that they had not been affiliated with any tribe of Indians other than the Eastern Cherokee or the Cherokee Nation.” [Source: page 4, 3rd paragraph of NARA document Eastern Cherokee Applications of the U.S. Court of Claims, 1906-1909.]

The collection at Fold3 titled “Eastern Cherokee Applications” contains these applications submitted to prove eligibility. [Important: Because this act was about money allocation and individuals filling out these applications would have received money if approved, this may raise the question, “Did our ancestor have a reason to lie or exaggerate the truth so that they might be awarded funds?” Further, the Genealogy Standards produced by the Board for Certification of Genealogists (BCG) reminds us: “Whenever possible, genealogists prefer to reason from information provided by consistently reliable participants, eyewitnesses, and reporters with no bias, potential for gain, or other motivation to distort, invent, omit, or otherwise report incorrect information.” [2] In this case, those filling out the Eastern Cherokee Applications did have potential for gain. So, be sure to take any genealogical data, like names, dates, and places, with a grain of salt and find other documentation to back-up the facts.]

The first step in locating whether your ancestor applied is to check the index. If you are not a member of Fold3.com, you will first need to go to www.fold3.com. Click in the center of the homepage where it says, “Free Access to Native American Records.” Next, on the left you will see “Records from Archives.” Go ahead and click that.

From the list now showing on your screen, choose “Eastern Cherokee Applications.” Then click “learn more” at the bottom right of the collection description.

From the new screen, choose “Browse by title.”

Notice, there are two general indexes. The first choice is for surnames between the letters of A and K, and the second general index is for the letters between L and Z. The index is alphabetical by surname.

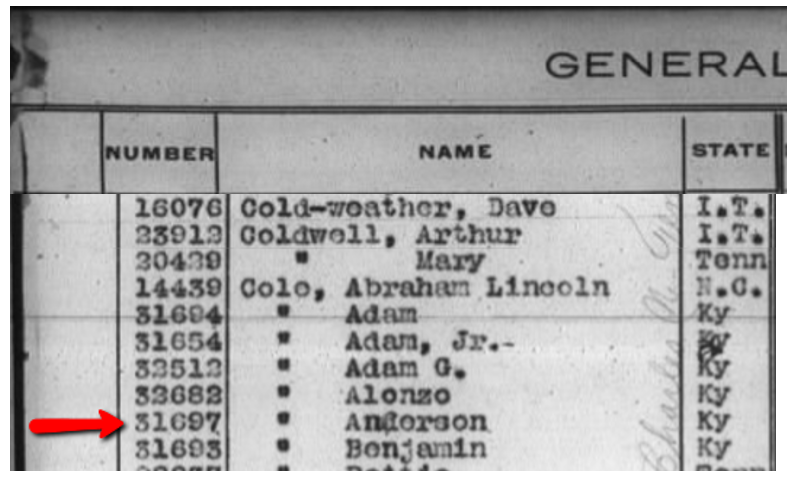

Scroll through the digital images of the index and find the surname of your targeted ancestor. For example, my ancestor’s last name is Cole.

You will see the state they were currently living in and a number listed to the left of each name. This number is what you will need to find the application of your ancestor. In the example here on the left, Anderson Cole’s number is 31697. Though the step of using this index could be omitted, I wanted you to know how to use it.

Anderson Cole’s name appears on the General Index of the Eastern Cherokee Applications.

Armed with this number as confirmation, let’s go back to the list of options and this order medication online for pain time, choose Applications.

Applications are broken down by the first letter of the surname, so in my case, I would click on the letter C and then from the new options list, click the appropriate indicator until I reach Anderson Cole.

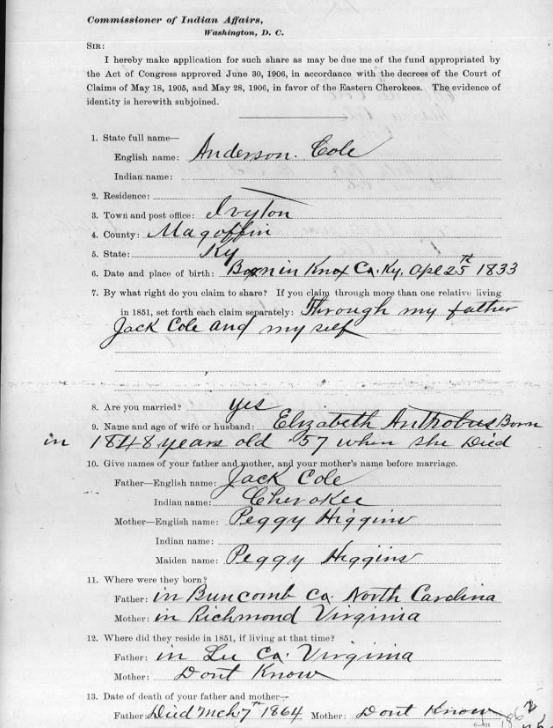

Anderson’s application is eight pages, however applications vary in size from fewer than eight to several more.

From Fold3.com, you can see each page of the application. Some of the information you may find on the applications include, but is not limited to: name, birth date and location of applicant, names of parents and siblings, name of spouse and marriage date and place, tribe affiliation, Cherokee name, grandparents names, and residences.

The application was sent in to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs and then it was decided whether the applicant was eligible or not.

Lies and Rejection

Anderson Cole’s Eastern Cherokee Application was rejected but held genealogical data.

In Anderson Cole’s case, he was rejected. This is found on the very first page of the application. In other words, the commission did not find him able to prove his relationship with known members of the Eastern Cherokee tribe and therefore, he was not given any allotment of money. This rejection neither proves or disproves whether Anderson was of Native American descent. However, it does suggest that something in his lineage was questioned.

Further, when reviewing the information recorded on any genealogy record, we must ask the question, “Did this person have any reason to lie?” When money is on the line, lying is always a possibility. According to further research, it appears Anderson either lied, omitted details, or was seriously mistaken about many names and dates of close family members. Even then, there are some great hints within the pages of his application and I was happy to find it.

Additional Information in the Eastern Cherokee Applications

In addition to an application being filed for our ancestor, if the ancestor had children under the age of 21, they may have also applied in behalf of the child as a Cherokee Minor.

Anderson’s son, W.T. Cole, applied under the same application number as Anderson. I found his application in the last pages of Anderson’s file. This type of record is direct evidence of a parent/child relationship and can be a wonderful substitute when other vital records can not be located. However, direct evidence (which is anything that directly answers a specific question…like ‘who are the parents of W.T. Cole?’) does not have to be true. In this case, just because Anderson says his son is W.T. Cole, doesn’t mean it is absolutely true. We should always find other records or evidence to back up our findings.

How is the Roll of Eastern Cherokees Different from the Eastern Cherokee Applications?

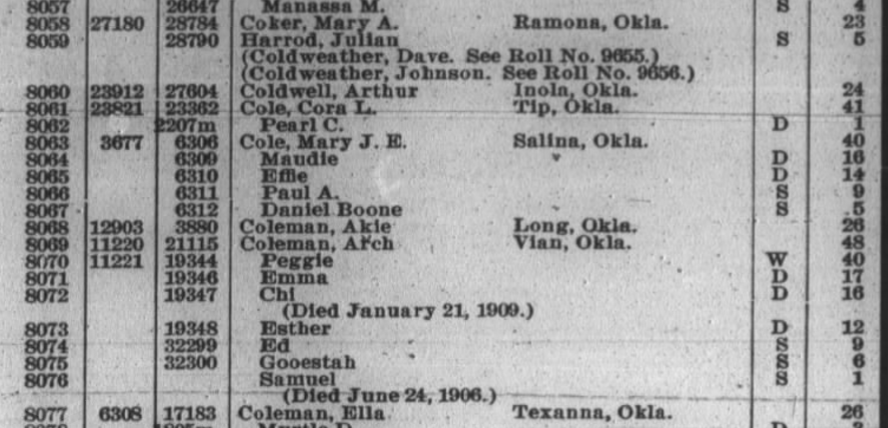

You may have noticed that besides the Eastern Cherokee applications and general index, there is also a record set titled “Roll of Eastern Cherokees.” Another name for this roll is called the Guion Miller Rolls. This is a roll, or list, provided by commissioner Guion Miller of all those who were approved to receive the allocated money. [We will be discussing the Guion Miller Roll Collection from Fold3 in a later blog post. Be sure to sign-up for our free newsletter so you don’t miss it!]

Anderson Cole and his son do not appear on this Roll of Eastern Cherokees. If however, your ancestor does, additional information on this roll could include application number, the names of minor children, ages of all parties, current residence, and a death date.

A partial page of the Roll of Eastern Cherokee found online at Fold3.com.

More on Native American Research

Using Native American collections for genealogy research can be challenging. We hope this has helped you to better understand the ins and outs for using the record collections at Fold3. For even more helpful tips, read:

How to Use the Dawes Collections for Native American Research

Stay tuned as we bring you additional instructions for exploring the Guion Miller Roll and Indian Census Rolls at Fold3.com in the days to come. Sign up for our free Genealogy Gems newsletter for our upcoming posts on this important subject.

Stay tuned as we bring you additional instructions for exploring the Guion Miller Roll and Indian Census Rolls at Fold3.com in the days to come. Sign up for our free Genealogy Gems newsletter for our upcoming posts on this important subject.

Article References:

[1] “The U.S. Eastern Cherokee or Guion Miller Roll,” article online, FamilySearch Wiki (https://familysearch.org/wiki/en/The_U.S._Eastern_Cherokee_or_Guion_Miller_Roll : accessed 1 Nov 2016). [2] Genealogy Standards, 50th anniversary edition, published by Board for Certification of Genealogists, 2014, standard 39, page 24.Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links and Genealogy Gems will be compensated if you make a purchase after clicking on these links (at no additional cost to you). Thank you for supporting Genealogy Gems!

How to Find and Use Land Records for Genealogy

Land records are some of the most underutilized, yet most useful, records available in genealogy. Often, they are the only records which state a direct relationship between family members. They can also be used to prove relationships indirectly by studying the land laws in force at the time. Sometimes they can even be used to locate an ancestor’s farm or original house, so that we can walk today where our family walked long ago.

Land records exist in the United States in abundance for most locations. Read on to learn how to find land records and how they can help you scale seemingly impossible brick walls in your genealogy research. Our guest blogger is Jaye Drummond, a researcher for Legacy Tree Genealogists.

The History of Land Records

The search for new land is one of the main themes of American history, so it makes sense that land records would be an important part of researching that history.

The right to own real estate was not universal in most of the countries from which the majority of American immigrants came. And even when it was possible to own land legally, it was often too expensive and thus out of reach for most people.

As a result, the lure of vast expanses of relatively cheap and plentiful land has proved irresistible to millions of immigrants to American shores over the course of the past 400 years.

The land records created throughout those years to document ownership of all that real estate have accumulated in seemingly limitless amounts. Even in the face of catastrophic record loss in some locations, land records are generally plentiful. They usually exist from the date of formation of colonial, state, and county governments, where the records still exist.

Information Contained in Land Records

Due to the paramount importance of land ownership in what would become the United States, land records often are the only records in which you will find your ancestors mentioned in some areas.

And there’s good news! Land records often state relationships or provide other, indirect, evidence of family relationships. This makes them an invaluable resource for genealogists.

Understanding what kinds of land records exist, where to find them, and how to use them is often critical to solving genealogical mysteries.

4 Types of Land Records and How to Use Them

There are four different types of land records that can play a vital role in your family history research. Let’s take a closer look at what they are and how to use them.

1. Land Deeds

The most essential land record is the deed. Deeds document the transfer or sale of title, or ownership, of a piece of land or other property from one party to another.

Deeds usually concern land, or “real” property, but they also often mention moveable or “chattel” property, such as household goods and even enslaved persons.

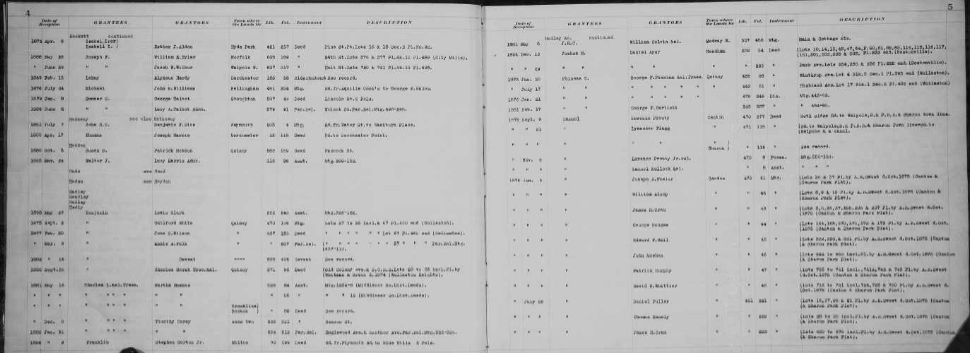

Example of deed index, courtesy of FamilySearch

They sometimes, but not always, contain explicit, direct statements of relationship between family members. Sometimes this can be a parent-child relationship, but deeds can also include a list of people who are children or heirs of a particular deceased person who owned the land being sold.

Sometimes the language in deeds involving heirs makes it clear that the heirs are children, sometimes not, so some care must be taken not to assume that all heirs are children. Research in other records sets such as probate, census, and church records may make the relationships of the heirs to the deceased land owner clearer.

In the early years of a settlement, and sometimes later, deeds books also often contained other types of transactions, including the sale of enslaved persons and sometimes even wills. These are often records for which no other copies survive. Thus, surviving deed books should always be checked for ancestors and their family members in every jurisdiction in which you do genealogy research.

Also, remember to check published abstracts of deeds if they exist, as witnesses to deeds were not included in most indexes to the original deed books. Witnessing a deed was one of many ways relatives assisted one another, and thus the presence of one of your ancestors as a witness for someone else suggests they had some kind of relationship, which might lead to the discovery of previously unknown ancestors.

Also keep in mind that not all states required the recording of deeds throughout their history, or did not require them to be recorded in a timely fashion.

Pennsylvania is an example of this lackadaisical attitude to record keeping that now seems foreign. When researching land records in Pennsylvania it is important to remember that deeds for an ancestor might have been recorded years, even decades, after the actual transaction took place. Therefore, always remember to check the indexes for deeds and other transactions many years after the person in question died or left the area.

In other states, such as New Jersey, land was sold at the colony and state level for longer than is typical in other areas and thus land records must be sought at the state or colony level up to that time.

In the case of New Jersey, deeds only began to be recorded in the various counties around 1785. Therefore, New Jersey real property research must be done at both the county and state or colonial level.

In the case of colonies and states with massive record loss, such as Virginia, land records recorded on the state level are often the only records that survive for some counties, and thus are critical for success in navigating such “burned” counties.

2. Land Grants and Patents

Land grants and patents issued by the various colonial, state and federal governments are also an important resource, including land lotteries in states like Georgia.

In many states, such as Pennsylvania and North Carolina, the original applications, warrants, surveys, and patents or grants still exist and can be searched at the state archives or online.

While these documents do not often state relationships, they sometimes do. That was the case with one of my ancestors whose father had applied for a land patent in Pennsylvania in 1787. He died before the patent was issued in 1800, and thus it was granted to his son by the same name. However, the land patent spelled out that the original applicant had died and his son was the person actually receiving the patent.

Land patents and grants, as well as deeds in general, can also document the dates in which an ancestor resided or at least owned land in a given location. This can assist the researcher in establishing timelines for ancestors. It can also help when it comes to differentiating between two or more individuals residing in a given area with the same name. Anyone dreading research on their Smith and Jones ancestors might just find the solution they seek in those old, musty deed books!

3. Mortgages

Other land records that might prove essential in solving genealogy puzzles are mortgages.

In some states like New Jersey, mortgages were recorded locally earlier than deeds and sometimes survive for earlier years than do deeds.

A mortgage is a promise by a borrower to repay a loan using real estate as collateral—in effect deeding title to the real estate to the creditor if the loan is not repaid.

A similar instrument called a deed of trust, or trust deed, performs the same function with the exception that a third-party trustee takes title if the loan is not paid back in full. In the early years, mortgages and trust deeds were usually contracted with private individuals, but as the banking industry grew in the United States over the course of the nineteenth century, they began to be taken out with banks instead of private persons.

The two parties involved in a mortgage are the “mortgagor” and the “mortgagee.” Indexes can often be found for mortgages using those terms.

However, sometimes early mortgages and trust deeds were recorded in the same books as deeds, so keep an eye out for them.

And remember: the mortgagor is the borrower, while the mortgagee is the creditor.

Don’t be put off by their sometimes-confusing terminology. Old mortgages and trust deeds are some of the most underused land records in existence—yet they can sometimes be the key that unlocks the door to that next ancestor. Don’t overlook them!

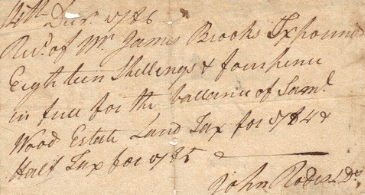

4. Tax Records

One other land record that could crack the case is land tax records. Everyone who owned land had to pay taxes on it, at least in theory. Sometimes, land tax books include notations about one person inheriting land from another, or more commonly, the change in owner’s name from one year to the next can indicate inheritance of the land. The absence of a deed or will showing the transfer might be explained by checking the land tax books.

“14th Dec. 1786 Received of Mr. James Brooks Six pounds, Eighteen Shillings and four pence in full for the balance of Samuel Wood Estate Land Tax for 1784 & Half tax for 85.” John Rodes L. Ds. Image courtesy of MyHeritage.

The Law of the Land: Primogeniture and Genealogy

In some cases, the inheritance and real estate laws of the time might allow you to make a determination of parentage even without a will or deed stating the suspected relationship.

The legal concept of primogeniture, or inheritance of land by the first-born son, was in force in many parts of the Thirteen Colonies until soon after independence, especially in the southern and middle colonies. Thus, when a land owner died, his first-born son would often inherit all or most of his land if he died intestate, or without a will.

The emergence of one man as the owner of a given piece of land in place of the previous owner, either as the seller, or “grantor,” in a deed or in the land tax records, could indicate that the previous owner died and the land was inherited by his “heir-at-law,” the first-born son. There might not be any record of this transfer, so knowing the “law of the land” can prove to be instrumental in cracking the case.

In these and many other ways, land records can be used to find direct and indirect evidence of family and other types of relationships, often when no other record does—or even survives. It is for this reason that land records research must be part of any reasonably exhaustive genealogical investigation.

Where to Find Land Records

In some areas, land records are the only records that survive which state relationships or can be used to provide indirect evidence of them.

They also are useful in establishing biographical timelines for ancestors, and to learn more about their lives. They can sometimes also be used to identify the location of ancestor’s farms and sometimes even their original homes, so that today’s genealogists can often literally walk in the footsteps of their ancestors. But where are those records now?

It used to be that if you wanted to do genealogy the right way, one of your first stops had to be at the county courthouse where your ancestors lived. This is still a good practice, as many treasures held within the walls of the hundreds of courthouses scattered across this land are not microfilmed, digitized, or abstracted, and likely never will be.

The Recorder of Deeds and the County Clerk are therefore often the genealogist’s best friends. So, planning a trip to the courthouse or archive where land records are held is still a good idea.

Smyth County, VA courthouse records (Image credit: Margaret Linford.)

But many of us live far away from where our ancestors owned land and lived out their lives. How can we access these records if we don’t have the time or budget to travel to the areas in question?

Thankfully, the digital revolution has made researching land records and other types of documents much easier, but often still time consuming and at times overwhelming.

The land records held at the state level for “state land” states (the original thirteen colonies and the states formed from them such as Maine and Kentucky) are usually indexed. They can often be accessed digitally at the website for the state archives, commercial genealogy sites such as Ancestry.com, or can be ordered via correspondence with the archive.

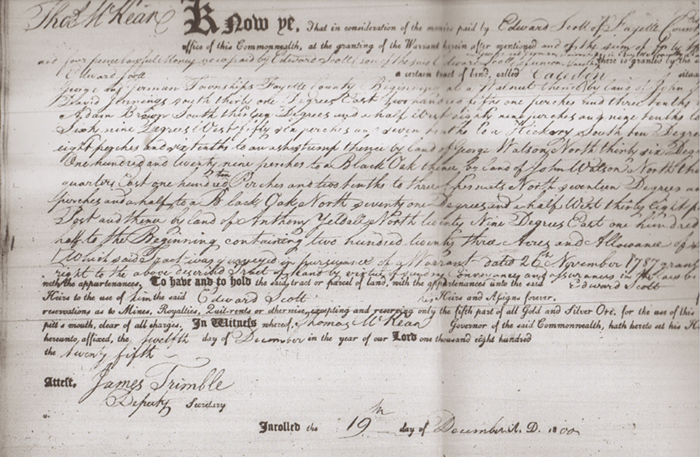

In states that were part of the old Northwest Territory, such as Ohio and Indiana, as well as the other public land states (any state formed under the Constitution that was not carved out of one of the original colonies), grants from the federal government to the first recorded owner of that land can be found at the Government Land Office site created by the Bureau of Land Management. Their website (available here) allows searches for names of individuals who purchased federal land in public land states. You can even view the digital images of the land grants, including the signature of the President of the United States at the time.

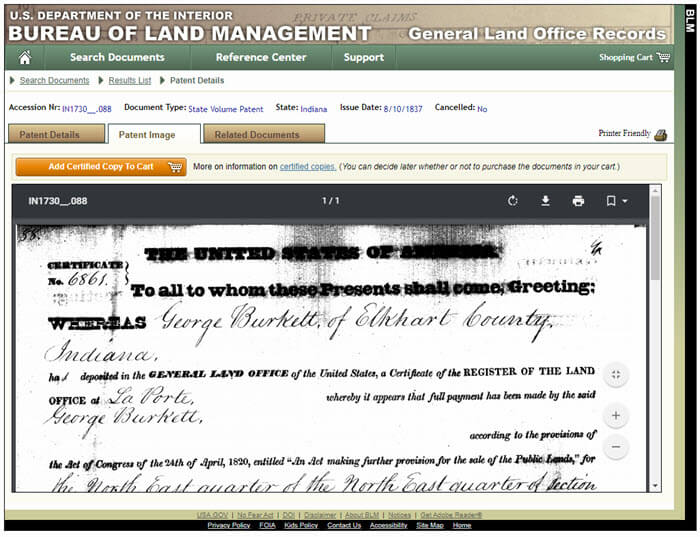

Example of a land patent image.

Other types of records associated with federal land, include:

- applications for public domain land grants,

- Homestead Act applications,

- Freedman’s Bureau land records,

- and bounty land warrants and applications for veterans.

These are all held at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. Many of these records also state relationships and add rich detail about the lives of ancestors. However, most of these records have never been digitized and must be searched in person or requested via the National Archives’ online order service.

(Editor’s note: Learn more about land records at the National Archives here.)

Land records at the county or town level are still held at the local county courthouse or archive, if they survive. Many jurisdictions have digitized their land records and made them available online, in many cases for free. This can sometimes include the entire run of a county’s land records, back to the formation of the county. County clerks and recorders will also sometimes do research via correspondence, though most are unable to do so due to time constraints.

Land Records at FamilySearch

Most importantly in the field of land records research from a genealogical perspective is the massive digitization project undertaken by FamilySearch, the website for the genealogical Society of Utah.

Millions of land records from all across the United States, and even some from other countries, are available at their website free of charge—and viewable either from the comfort of your own home or at a Family History Center or the Family History Library itself, depending on the license agreement FamilySearch has with the original repository.

This vast trove of land records is almost completely unindexed by FamilySearch and will thus not appear in results using their “Records” search page. They must instead be searched in the “Catalog” search page. (Editor’s note: learn how to search unindexed records at FamilySearch by reading our article: Browse-Only Databases at FamilySearch are Easy to Use.)

Despite not being indexed by FamilySearch, the digitized microfilms themselves usually have indexes, either in separate volumes or at the beginnings or ends of the digitized individual deed books.

Most of the digitized land records made available by FamilySearch date from 1900 or before, so a trip to the courthouse might still be warranted for most twentieth-century deeds and more recent land records research. If all else fails, don’t forget to ask the recorder or clerk for help if you have a limited research goal, such as one deed copy—you just might be surprised how eager and willing they are to help.

If the land records you need are unavailable online or are held in a remote location, consider hiring a professional genealogist to go to the courthouse in person on your behalf. Legacy Tree Genealogists has a worldwide network of onsite researchers who can obtain nearly any record that still exists in most areas. Learn more here about how we can assist you in the search for your ancestors and the records of their sometimes only tangible piece of the American dream—land!

(Editor’s note: Our links to Legacy Tree Genealogists are affiliate links and we’ll be compensated – at no cost to you – if you use it when you visit their website. This page includes a discount code for full service projects, or scroll to the bottom of the page for information about their 45-minute genealogy consultations. Thank you for helping to keep our articles and the Genealogy Gems Podcast free. )

Indeed, land ownership was more widespread in the Thirteen Colonies and the United States than most any other nation on earth. So the good news is that there’s a good chance that some of your ancestors were land owners. However you access them, land records are absolutely critical for success in genealogy and should be thoroughly examined whenever possible. You’ll be glad you did.

Jaye Drummond is a researcher for Legacy Tree Genealogists, a worldwide genealogy research firm with extensive expertise in breaking through genealogy brick walls. To learn more about Legacy Tree services and its research team, visit their website here.