by Lisa Cooke | Apr 10, 2013 | 01 What's New, Records & databases, Research Skills

It’s time to pay taxes in the United States!  Is it any consolation that our ancestors paid them, too? Here’s a brief history of U.S. federal taxation and tips on where to find tax records for the U.S. and the U.K.

Is it any consolation that our ancestors paid them, too? Here’s a brief history of U.S. federal taxation and tips on where to find tax records for the U.S. and the U.K.

History of Tax Records

According to the National Archives (U.S.), the Civil War prompted the first national income tax, a flat 3% on incomes over $800. (See an image of the 16th Amendment and the first 1040 form here.)

The Supreme Court halted a later attempt by Congress to levy another income tax, saying it was unconstitutional.

In 1913 the 16th Amendment granted that power. Even then, only 1% of the population paid income taxes because most folks met the exemptions and deductions. Tax rates varied from 1% to 6%–wouldn’t we love to see those rates now!

Where to Find Tax Records

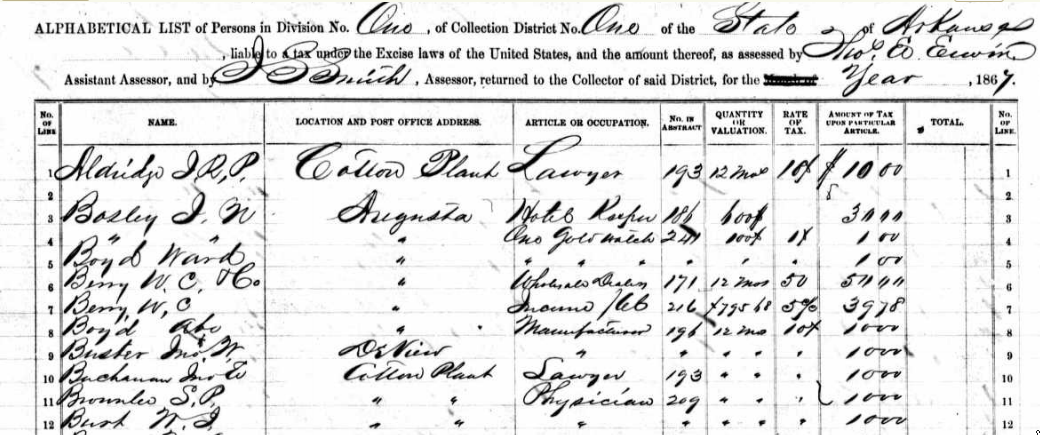

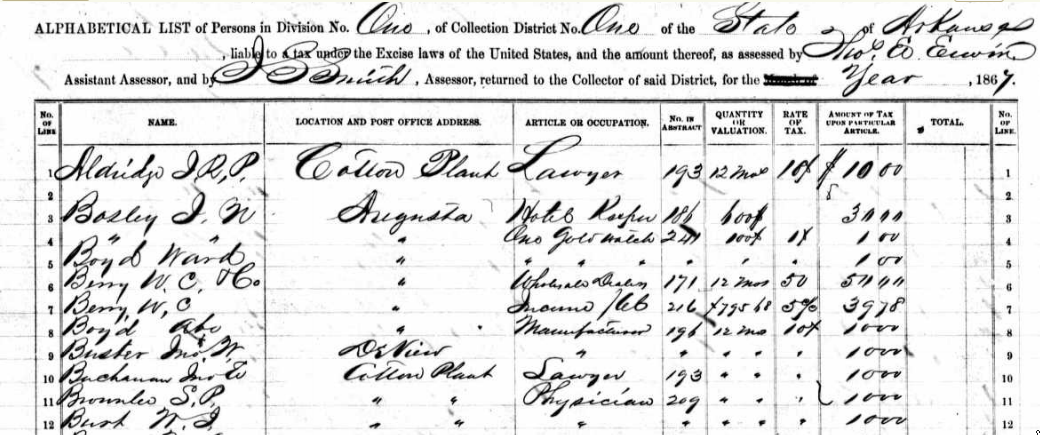

Ancestry.com has indexed images of U.S. federal tax assessment lists from the Civil War period (and beyond, for some territories).

Here’s a sample image from Arkansas:

Of course, the U.S. federal income tax is just one type. Taxes have been levied on real estate, personal property and income by local, regional and national governments throughout the world.

Some tax records can be found online at the largest genealogy websites.

Here are examples of tax records that can be found at Ancestry:

- tax records from London (1692-1932);

- the U.S. states of Pennsylvania, Tennessee, New York, Ohio, Georgia and Texas;

- and many from Scotland, Ireland, Canada and Russia (there’s more: see a full list and descriptions here).

FamilySearch.org hosts over a million records each of U.S. state tax records from Ohio and Texas.

FindMyPast hosts a wealth of U.K. tax records, from local rate books to Cheshire land taxes and even the Northamptonshire Hearth Tax of 1674.

In addition to genealogy websites, here in the U.S., look for original real estate and personal property taxpayer lists in county courthouses or state archives.

It’s also a good idea to consult genealogical or historical organizations and guides. A Google search for “tax records genealogy Virginia” brings up great results from the Library of Virginia and Binns Genealogy. And here’s a search tip: Use the keyword “genealogy” so historical records will pop up. Without that term, you’re going to get results that talk about paying taxes today.

If you still haven’t found the tax records you are looking for, there are two more excellent resources available for finding out what else might be available within a particular jurisdiction.

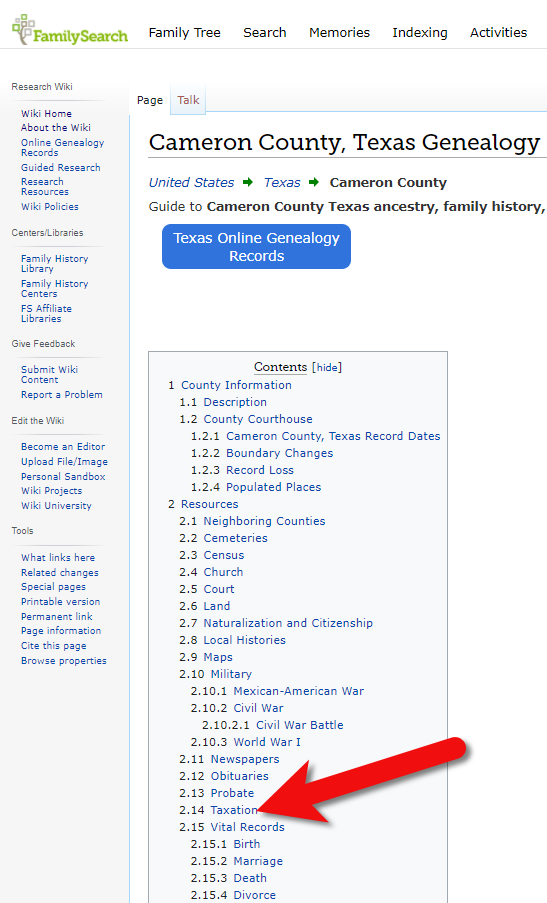

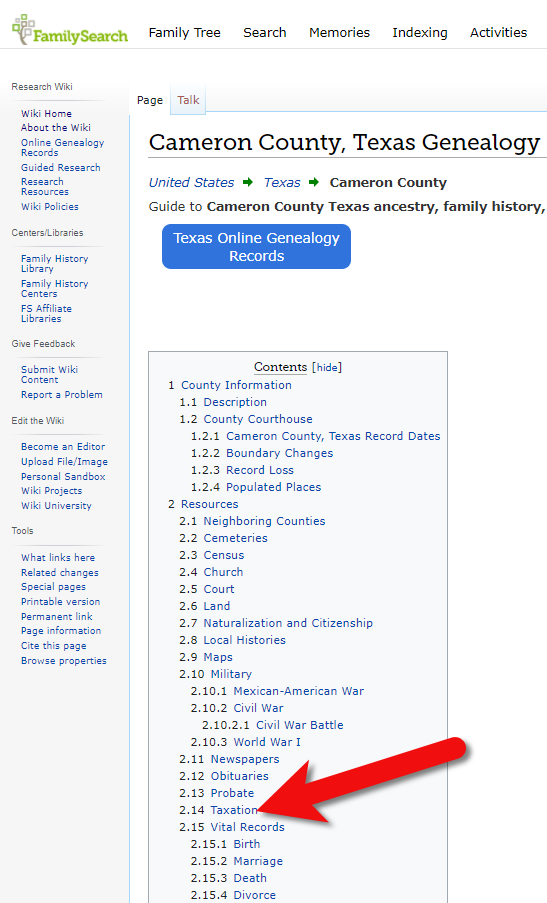

The first is the FamilySearch Wiki. From the home page you can drill down using the map, or try a search in the search box. Search for the jurisdiction and the keyword tax. Click through to the page for that jurisdiction. Typically you will find a table of contents that includes links to the section of the page covering various topics. Look for a link to tax, taxes, tax records, or taxation. They will list known sources for tax records in that area.

Tax records at the familysearch wiki

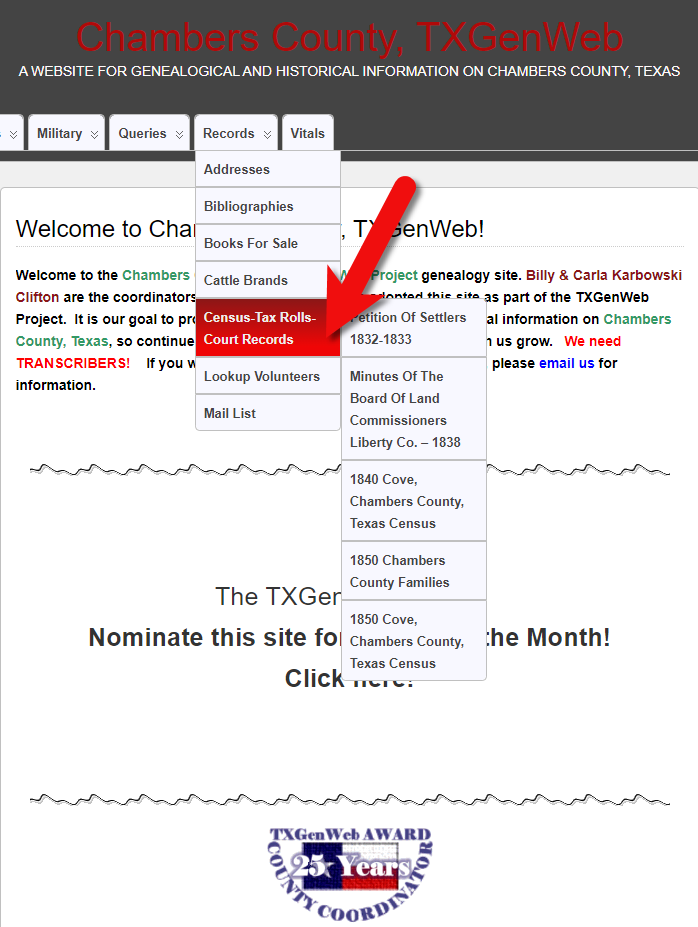

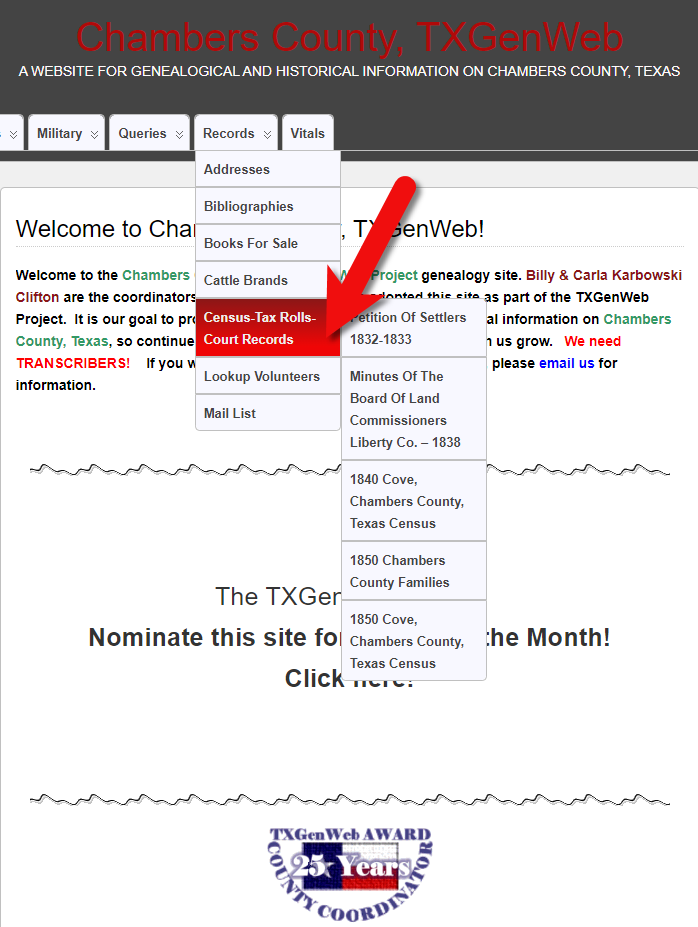

The second resource for finding out what else might be available is the free USGenWeb site. Like the FamilySearch Wiki, it’s organized by location / jurisdiction. Drill down to the place and then look for the section listing the known records for that area and look for tax related links.

Find information about tax records at USGenWeb

Why It’s Worth Finding Tax Records

I’ll leave you with this tantalizing list of data gathered in the Calhoun County, Georgia tax list of 1873. It enumerates whites, children, the blind/deaf/dumb, dentists, auctioneers, and those who have ten-pin alleys, pool tables and skating rinks. Then, real estate is assessed in detail. Finally, each person’s amount of money, investments, merchandise, household furniture, and investment in manufacturing is assessed.

As you can see, it can pay you big to invest time in looking for your ancestor’s tax records! Just make sure that if you’re here in the U.S., you’ve got your own taxes out of the way before you go searching for someone else’s.

by Lisa Cooke | Apr 24, 2015 | 01 What's New, British, Church, images, Military, Records & databases, United States

Every Friday, we highlight new genealogy records online. Scan these posts for content that may include your ancestors. Use these records to inspire your search for similar records elsewhere. Always check our Google tips at the end of each list: they are custom-crafted each week to give YOU one more tool in your genealogy toolbox.

Every Friday, we highlight new genealogy records online. Scan these posts for content that may include your ancestors. Use these records to inspire your search for similar records elsewhere. Always check our Google tips at the end of each list: they are custom-crafted each week to give YOU one more tool in your genealogy toolbox.

This week:

ALABAMA COUNTY MARRIAGES. Over 700,000 names have been added to FamilySearch’s index of Alabama county marriage records (1809-1950). Some of the index entries have images.

ENGLAND PARISH RECORDS. Indexes to baptisms, marriages and burials from Derbyshire (1538-1910) and images of original records of Yorkshire baptisms, bishop’s transcripts of baptisms, marriage banns, marriages, bishop’s transcripts of marriages, burials and bishop’s transcripts of burials (1500s-19oos, dates vary) are now searchable on FindMyPast.

IOWA HISTORICAL JOURNALS. The State Historical Society of Iowa has posted back issues of The Annals of Iowa dating to 1863. This is a quarterly, peer-reviewed historical journal. Use the search box to see whether your Iowa ancestors, hometowns or other family connections (schools, churches, friends, etc) are mentioned in more than 150 years’ worth of articles.

RUSSIAN WWII SOLDIERS. According to this article, “Thanks to a new online state initiative, families of Russian WWII combatants…are now able to give their forebears the recognition they deserve, 70 years on. The Zvyezdy Pobedy project, organized by the Rossiyskaya Gazeta newspaper, allows the descendants of those who fought in the Red Army in WWII to find out whether their ancestors were among the recipients of over 38 million orders and medals awarded during the war….There are more than 8,200 names listed in the database, which can be read in Russian at rg.ru/zvezdy_pobedy.”

U.S. CIVIL WAR RECORDS. These aren’t new, necessarily, but until April 30, Civil War records on Fold3 are FREE to search! Among the 43 million items are (of course!) military records, personal accounts, historic writings, photographs and maps. Both Union and Confederate records are represented.

Google tip of the week: Need to read web text in Russian or another language you don’t know? Use Google Translate to translate short passages or even entire webpages! Copy text or a URL (for full page translation) into the left box, then click English and Translate on the right. You can even play back an audio version of the foreign text to hear how it sounds! Learn more in Lisa Louise Cooke’s The Genealogist’s Google Toolbox. The 2nd edition, newly published in 2015, is fully revised and updated with the best Google has to offer–which is a LOT.

by Lisa Cooke | Mar 19, 2014 | Beginner

Free Family History has a nice ring to it!

Free Family History has a nice ring to it!

Did you know you don’t have to pay for a subscription to anything to be able to start learning more about your family history?

Start to find your family history for free by asking the four questions listed below.

1. What do you already know?

Chances are that you know something about your family already. The most important facts we start with are our relatives’ names and their dates and places of birth, marriage(s) and death. These facts can help you later to distinguish between records about our relatives and others with the same name.

Write down what you know about your “direct ancestors”–your parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, etc.–on a family tree chart like this free fill-in pdf format (these are also called pedigree charts). Then use family group sheets like this one to organize facts about each individual couple (this is where you can list all the children your grandparents had, for example).

2. What do your relatives know?

After filling out what you can, show your family tree chart and family group sheets to other relatives. Ask them if they can fill in some blanks. Remember these tips:

- Try to include a little note about who tells you each piece of information.

- Someone may dispute what you find. Everyone’s memory of an event is different. Don’t argue. Treat their information with respect:. Write it down. Then ask politely if they have any documentation you could see, or why they believe something to be true (who told them, etc).

- Ask whether anything is missing from your charts: a grandparent’s second marriage, a stillborn child or even whether someone’s name is accurate. You or others might know someone by a nickname or middle name.

- Be sensitive to information that might be confidential or not generally well-known, like a birth date that doesn’t appear more than 9 months after a wedding, or a first marriage. Consider asking living relatives if it’s okay for you to share certain facts. Consider only showing part of your charts to a relative.

3. What’s in the attic (or anywhere else)?

We can often find family documents in our own homes and those of our relatives. Look in attics, basements, storage units, safe deposit boxes and  safes, filing cabinets, photo albums, scrapbooks, shoeboxes and other places where papers and memorabilia may be tucked. You’re looking for things like:

safes, filing cabinets, photo albums, scrapbooks, shoeboxes and other places where papers and memorabilia may be tucked. You’re looking for things like:

- certificates of birth, baptism, marriage or death;

- obituaries or other news articles, like anniversaries;

- funeral programs, wedding and birth announcements;

- photos with names or other notes on the backs;

- insurance, pension, military or other paperwork that may mention births or deaths or beneficiary information;

- wills and home ownership paperwork–even outdated ones;

- a family Bible.

When you find family names, relationships, dates and places in these documents, add them to your charts.

4. What’s available online for free?

There are two major types of family history information online: records and trees. Records are documents created about specific people, like obituaries, birth certificates and all those other examples I just mentioned. Trees are a computerized form of other people’s family tree charts and group sheets. It can be tempting to just look for someone else’s version of your family tree. Eventually you will want to consult those. But other people’s trees are notoriously full of mistakes! Instead, start by looking for records about the relatives you already have identified.

I suggest that you start your search at FamilySearch.org because it’s totally free. At most other sites, you’ll have to subscribe or pay to see all the search results. At FamilySearch, you just need to create a free user login to get the most access to their records.

After logging in, click Search. Choose a relative you don’t know a lot about. Search for that name. Use the different search options to add more information–even a range of dates and a state/province or country–so you don’t have to wade through thousands of near-matches.

The most common records to find on FamilySearch for many countries are census and vital records.

- A census is a tally of residents, voters or another target population. Entries often include details about a household: who lived there, how they were related, how old they were, where they were born, etc. You can often extract family information from census listings, though some things (like ages or name spellings) may not be totally accurate.

- Vital records are official records of someone’s birth, marriage or death. In these, you’ll often find important dates and places as well as names of parents, spouses or others important to the family. They aren’t always totally accurate, and you may only be able to see an index of the record (not the actual document).

As you find search results, compare what they say to what you’ve already learned. How likely is it that this record belongs to your family? Consider how many people seem to have the same name in that location and time period (for example, how many are mentioned in the 1880 U.S. census in that state?). Don’t just look at the search results list: click through to look at the full summary of the entry and, if you can, the original record itself. You may find additional details in these that can confirm whether this record belongs to your relative. You may even find out about new people: your great-grandparents’ parents, for example. Write it all down or begin building a family tree right there on the FamilySearch website (because it’s totally free: learn more about that here.) And one of the greatest keys to long term success is citing your sources. It’s imperative that you make careful note of where you got the resource so that you can find and refer to it again later, and back up your research if it is ever called into question.

People who research their family history often describe it as a puzzle with lots of different pieces. You will need to assemble a lot of puzzle pieces–information about each relative–to begin to see the “bigger picture” of your family history. You’ll start to sense which pieces may belong to a different family puzzle. You may put together a picture that is unexpected, or has some shadows and sadness. There will likely also emerge heroic, beautiful and touching images.

People who research their family history often describe it as a puzzle with lots of different pieces. You will need to assemble a lot of puzzle pieces–information about each relative–to begin to see the “bigger picture” of your family history. You’ll start to sense which pieces may belong to a different family puzzle. You may put together a picture that is unexpected, or has some shadows and sadness. There will likely also emerge heroic, beautiful and touching images.

Ready to learn more?

Up next, read:

7 Great Ways to Use Your iPad for Family History

How to Find Your Family Tree Online

Best Genealogy Software

Search the SSDI for Your Family History

Is it any consolation that our ancestors paid them, too? Here’s a brief history of U.S. federal taxation and tips on where to find tax records for the U.S. and the U.K.

Is it any consolation that our ancestors paid them, too? Here’s a brief history of U.S. federal taxation and tips on where to find tax records for the U.S. and the U.K.

Free Family History has a nice ring to it!

Free Family History has a nice ring to it! safes, filing cabinets, photo albums, scrapbooks, shoeboxes and other places where papers and memorabilia may be tucked. You’re looking for things like:

safes, filing cabinets, photo albums, scrapbooks, shoeboxes and other places where papers and memorabilia may be tucked. You’re looking for things like: People who research their family history often describe it as a puzzle with lots of different pieces. You will need to assemble a lot of puzzle pieces–information about each relative–to begin to see the “bigger picture” of your family history. You’ll start to sense which pieces may belong to a different family puzzle. You may put together a picture that is unexpected, or has some shadows and sadness. There will likely also emerge heroic, beautiful and touching images.

People who research their family history often describe it as a puzzle with lots of different pieces. You will need to assemble a lot of puzzle pieces–information about each relative–to begin to see the “bigger picture” of your family history. You’ll start to sense which pieces may belong to a different family puzzle. You may put together a picture that is unexpected, or has some shadows and sadness. There will likely also emerge heroic, beautiful and touching images.