by Lisa Cooke | Sep 16, 2017 | 01 What's New, Book Club, Libraries, Listeners & Readers, Mobile

Your local library may offer free genealogy magazines and ebooks. Why choose them over print? So many reasons! No more late fees. Read on the go. Choose your font size. So go ahead: check out digital versions of that Genealogy Gems Book Club title you’ve been meaning to read, or the current issue of Family Tree Magazine. Here’s how.

Here in the U.S., it’s my favorite time of year: back-to-school! The weather slowly cools. My children shake off summer’s mental lethargy. My own schedule resumes a more predictable, productive rhythm. And after months spent outdoors, I rediscover my local library. Top on my library list this fall: free genealogy ebooks and magazines I can check out on my mobile device. It’s on-the-go reading for my favorite hobby–with no searching under my bed when items come due to avoid those pesky late fees.

Free Genealogy eBooks and Magazines

Genealogy Gems Premium Member Autumn feels the same way about free genealogy gems at her local library. Here’s a letter she wrote to Lisa Louise Cooke:

“I’m really enjoying both the Premium and free podcasts. I also like the addition of the Genealogy Gems Book Club. I haven’t read all the books yet but am adding them all to my wishlist on Overdrive, a free app that allows you to check out digital books for free from your local library. They don’t have every book but they have many, many books including some from the book club. Most libraries have a lot of biographies and histories available through Overdrive for free that are of interest to genealogists as well. Some libraries are adding video to their Overdrive offerings too.

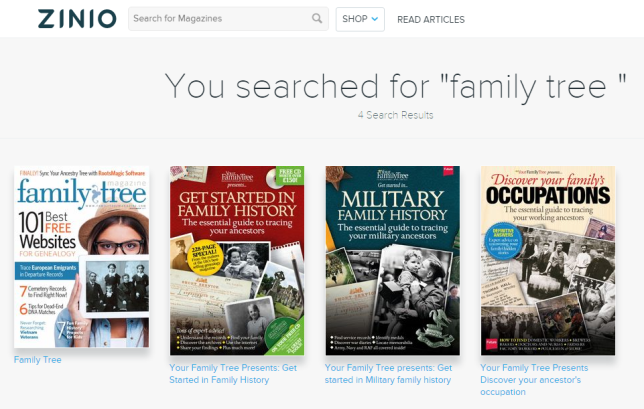

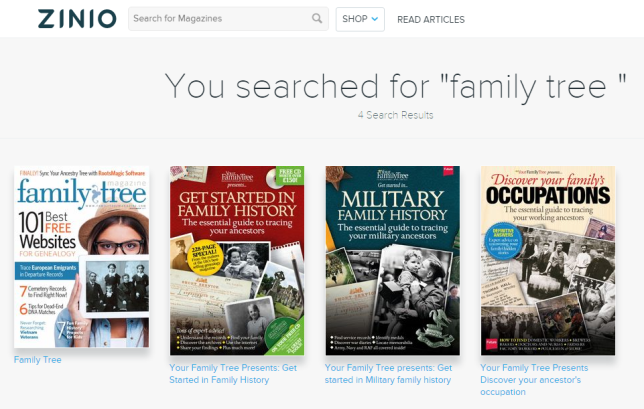

Many of these same libraries offer magazines free as well. My library…use[s] Zinio, a magazine app. I only subscribe to a couple of magazines now because I can get so many for free through my library (not to mention keeping my home neater by not having them laying everywhere).”

It makes me happy that Autumn is enjoying the Genealogy Gems Book Club. We hear from many avid readers who love browsing our list of mainstream fiction and nonfiction picks for family history lovers. As part of our book club, we interview every book club author, too–from beloved novelists like Fannie Flagg to acclaimed journalists, memoir writers, and historians who take their own unique approaches to family history themes. Hear excerpts of these interviews on the free Genealogy Gems Podcast; full interviews run on the Genealogy Gems Premium Podcast, available by subscription.

It makes me happy that Autumn is enjoying the Genealogy Gems Book Club. We hear from many avid readers who love browsing our list of mainstream fiction and nonfiction picks for family history lovers. As part of our book club, we interview every book club author, too–from beloved novelists like Fannie Flagg to acclaimed journalists, memoir writers, and historians who take their own unique approaches to family history themes. Hear excerpts of these interviews on the free Genealogy Gems Podcast; full interviews run on the Genealogy Gems Premium Podcast, available by subscription.

Overdrive and Zinio

At Autumn’s recommendation, I started using Overdrive through my local library. I love it! I’ve listened to several digital audiobooks on the road and at the gym through Overdrive and have read several ebooks, too. (I’m always on the hunt for the next Genealogy Gems Book Club title.) The books just disappear at the end of the lending period (hence the “no late fees” bonus).

Genealogy Gems Service Manager Lacey Cooke loves Overdrive, too. She sent me these four reasons why:

Genealogy Gems Service Manager Lacey Cooke loves Overdrive, too. She sent me these four reasons why:

1. Download for Offline Listening: “You can download the ebooks, audiobooks, magazines etc. to your device so that you can enjoy them offline (great for traveling). They’ll still disappear once your lending period expires, but having them available offline is awesome. You don’t have to worry about data charges or slow internet connections.

2. The Wishlist: Autumn briefly mentioned the Wishlist feature. I love this feature because it gives me somewhere to save book titles that I’m interested in reading at some point, but I’m not ready to check out just yet.

3. Bookmark/Syncing: You can bookmark a page, then pick up where you left off. If you have the Overdrive app on multiple devices, the app syncs. I can start reading on one device, and pick up on another right where I left off.

4. Format Adjustments: You can adjust the font style, size, and color to make it easier for you to read. I like to pick a nice, clean font in a big size so there’s no strain on my eyes.”

It’s worth noting that if you don’t already have a library card with your local library, you may be required to sign up in person to get a card, even if you only plan on using the Overdrive app to request items online. New releases or popular titles may have a wait list to check out the ebook or audiobook (especially if the library only possesses one copy). If you do have to place an ebook on hold, you will be notified via email when it becomes available to you, so if you don’t check your email regularly, keep that in mind when you place a hold. Each library system is different, so of course, your experience may vary.

Another helpful tip: not every library offers Overdrive ebook checkouts. But sometimes you can use another library’s Overdrive privileges. Autumn sent a link to these instructions on how to do so. (Thanks, Autumn!)

Autumn also mentioned the Zinio app. My library doesn’t offer Zinio yet, so I spent a little time on its public search portal. That doesn’t have a browsable genealogy category, and searches for the terms family history, genealogy and ancestry came up empty. But I did finally find these titles:

Lisa Louise Cooke, Genealogy Gems DNA expert Diahan Southard, and I are all frequent contributors to Family Tree Magazine, which we {heart} and recommend for its easy-reading research tips, hands-on tech and DNA tutorials, and the eye-candy layout.

More Free Genealogy Resources at Your Local Library

Of course, your local library may offer many additional free genealogy research and reading materials. Of tremendous value is access to Library editions of popular genealogy databases such as Ancestry, Findmypast, Fold3, and MyHeritage, along with institutional versions of historical newspaper databases. (Click here to learn more about the differences between the major genealogy websites.) Call your library or browse its website to see what resources may be available with your library card on site or even remotely from your own home or mobile device. And remember to watch for your library’s e-media options like those recommended by Autumn.

As a special shout-out to all the free genealogy resources at your library, Lisa Louise Cooke has granted free access for everyone to Genealogy Gems Premium Podcast episode #125. In this episode, Lisa has a full discussion about more free genealogy gems at public libraries with Cheryl McClellan. Cheryl is not only my awesome mom, she rocks professionally as the Geauga County, Ohio public library system staff genealogist!

As a special shout-out to all the free genealogy resources at your library, Lisa Louise Cooke has granted free access for everyone to Genealogy Gems Premium Podcast episode #125. In this episode, Lisa has a full discussion about more free genealogy gems at public libraries with Cheryl McClellan. Cheryl is not only my awesome mom, she rocks professionally as the Geauga County, Ohio public library system staff genealogist!

This Premium episode is usually exclusively for Genealogy Gems Premium members. If you love it, and you’re not already a member, consider gifting yourself a “back to school” subscription. It’s the most fun, energizing, apply-it-now genealogy learning experience you may ever have.

by Lisa Cooke | Apr 24, 2019 | 01 What's New, Trees |

In this post I’m going to answer common questions about the best strategy for creating and maintaining your family tree data.

Should I build my family tree online?

This is a question I get in various forms quite often from Genealogy Gems Podcast listeners. But there’s really more to this question than meets the eye. Today’s family historian needs a master game plan for how they will not only build their family tree, but where they will build it, and where they will share it.

On the podcast I describe it this way:

Plant your tree in your own backyard and share branches online.

I’m going to explain what I mean by this by starting at the beginning.

When You Start Your Family Tree

If you’re new to researching your family’s history, you probably started out with one of the big genealogy websites, such as Ancestry, MyHeritage, Findmypast, or FamilySearch. I refer to them as the Genealogy Giants because they have millions of genealogical records, and they offer you the tools to build your family tree on their website. (Learn more about what each of the Genealogy Giants websites have to offer here in this handy comparison guide.)

These sites make it easy to start entering information about yourself, your parents, and your grandparents either on their website or through their mobile app. But should you do that?

My answer is, “not so fast!” Let’s think through the long-term game plan for this important information that is your family’s legacy.

Family is Forever

Genealogy is a hobby that lasts a lifetime. It’s nearly impossible to run out of ancestors or stories to explore.

But have you noticed that websites don’t last forever? And even if they do, their services and tools will undoubtedly change over time.

And there are many, many genealogy websites out there. A large number of them will encourage you or even require you to start creating an online family tree on their site in order to get the most value from the tools that they offer for your research.

As you work with these different genealogy websites, you may start to feel like your tree is getting scattered across the web. It’s easy to find yourself with different versions of your tree, unsure of which one is the most accurate and complete version.

It’s this inevitable situation that leads to my conclusion that you build and protect a master version of your family tree. I’m not suggesting that you can’t or shouldn’t use an online tree. In fact, regardless of whether you do, you need a “Master Family Tree.”

Plant Your “Master Family Tree” in Your Own Backyard

What do I mean when I say that you should plant your “master family tree” in your own backyard? I’m talking about using a genealogy database software program that resides on your own computer. Let’s explore that further.

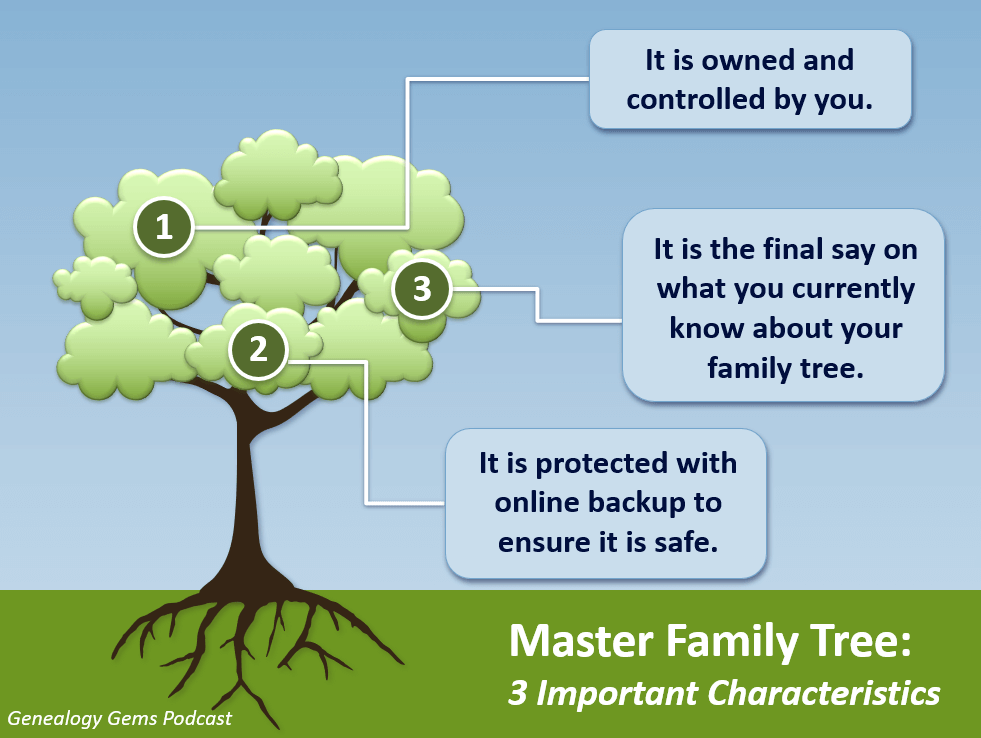

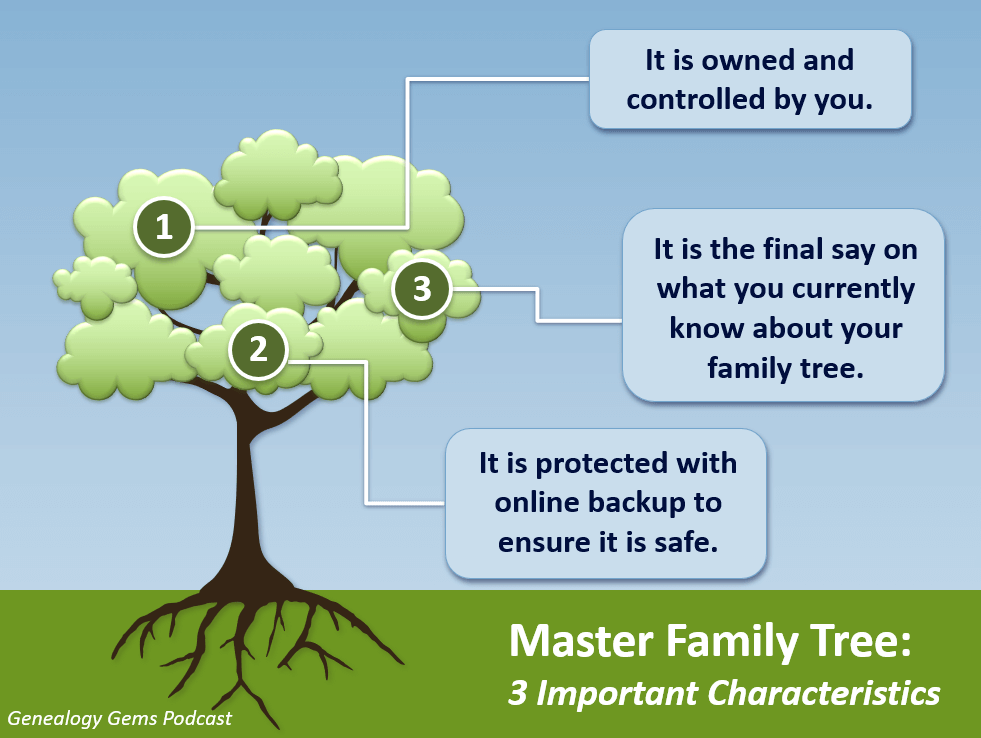

A master family tree has three important characteristics:

- It is owned and controlled by you.

- It is the final say on what you currently know about your family tree.

- It is protected with online backup to ensure it is safe.

Your Master Family Tree

1. Your master family tree is owned and controlled by you.

If you create an online family tree on a genealogy website (or in the case of FamilySearch’s global online tree, you add your information to it) you have given final control of that information to the company who owns the website.

In order to own and control your tree, you will need a genealogy database software program installed on your own computer. I use RootsMagic (and I’m proud to have them as a sponsor of the Genealogy Gems Podcast) but there are other programs as well.

A genealogy database software program is installed on your computer. The program and the data you enter into it belongs to you and is under your personal control.

Genealogy databases allow you to not only easily enter data, but also to export it. If you wish to use a different program later, or add your existing data to an online tree, you can export your family tree data as a universally accepted GEDCOM file. (Learn more about GEDCOM files in this article.)

2. It is the final say on what you currently know about your family tree.

As you research your family tree, you will come to important conclusions, such as an ancestor’s birthdate or the village in which they were born. It can take a while to prove your findings are accurate, but once you do, you need one location in which to keep those findings. And most importantly, you must be able to cite the sources for that information. That one location for all this activity is your genealogy database.

However, the nature of genealogy research is that it can take some digging to prove the information is correct. During the process of that research you may find information that you aren’t sure about, and it can be helpful to attach it to the online tree that you have at the same website where you found the information. That gives you a way to hang on to it and keep researching. You can always remove it later. We’ll talk more about strategies for using online family trees a little bit later.

Once you are convinced that the information is correct, then its final resting place is your Master Family Tree. You enter the information and add source citations. This way, whenever you need an accurate view of where you are in your completed family tree research, you can turn to one location: your genealogy database software and the Master Family Tree it contains.

3. It’s protected with online backup to ensure it is safe.

Your family tree isn’t safe unless the database file is backed up to the cloud.

Who among us hasn’t had a computer malfunction or die?

It isn’t good enough to simply back up your computer files to an external hard drive, because that external hard drive is still in your house. If your house is damaged or burglarized, chances are both will be affected.

Another problem with backing up to an external hard drive is that they can malfunction and break. And of course, there is the problem of remembering to back it up on a regular basis.

Cloud backup solves all these problems by backing up your files automatically and storing them safely in an offsite location.

Cloud backup is actually very simple to install and requires no work on your part once it’s up and running. (We’ve got an article here that will walk you through the process.)

There are many cloud backup services available. I use Backblaze (which you can learn more about here). As a genealogist I have a checklist of features that are important to me, and Backblaze checked all the boxes.

Regardless of which service you choose the important thing is to not wait another day to set it up. This protection is a critical part of your Master Family Tree plan.

Using Online Family Trees

Now that you have your own database on your own computer that is backed up to the cloud for protection, let’s talk about strategic ways that you can use online family trees.

First, it’s important to realize that you don’t have to create a tree on a genealogy website just because they prompt you to do so. While there are benefits for you to doing so, the company who owns that website actually benefits tremendously as well.

In today’s world, data is very valuable. I encourage you to read the terms of service and other fine print (I know, it’s boring!) because it will explain the ownership and potential use of that data.

While it’s not the focus of this article, it’s important to understand that other industries are interested in family history data, and data may be shared or sold (with or without identifying information, depending on the terms).

But as I say, there are benefits to using online family trees. These benefits include:

- Hints – Online family trees generate research hints on the Genealogy Giants websites and some of the other websites that offer trees.

- Cousin Connection – Online family trees offer you an opportunity to possibly connect with other relatives who find your tree.

- DNA – Online family trees can now dovetail with your DNA test results (if you took a test with the company where your tree resides). This can offer you additional research avenues.

These benefits can be helpful indeed. However, problems can arise too. They include:

- Copying – When you tree is public other users of the website can copy and redistribute your information including family photos.

- Errors – If you discover an error in your tree, you may fix it, but chances are it has already been widely copied and distributed by other users.

- Email – If you have your entire tree online and your email notifications are active, you may receive an onslaught of hints for people in your tree. Often these are very distant cousins that you are not actively researching. And let’s face it, the emails can be annoying and distract your focus from your targeted research. For example, as of this writing at Ancestry.com you can’t select which ancestors you want to receive email hint notifications for. You can only select hints for the entire tree.

So, let’s review my strategy:

Plant your tree in your own backyard and share branches online.

Now that you’ve planted your tree in your own backed up software, let’s explore the ways in which you can share branches online.

Targeted Online Family Trees

Many people don’t realize that you don’t have to add your entire tree to a website. You can just add parts of your tree.

For example, I may just put my direct ancestors in my tree (grandparents, great-grandparents, and so forth). This can still be a fairly larger number of people. I may want to include their siblings because they grew up in the same household. But I can leave out the far-reaching branches and relatives that really don’t have a direct impact on that line of research.

You can also have multiple trees that focus on specific areas of your research that are important to you.

Exploratory Online Family Trees

Some genealogists also create trees that represent a working theory that they have. This type of tree can help expose where the problems or inaccuracies lie. As you research the theory and as hints arise it can become very clear that a relationship does not exist after all.

An exploratory tree is an excellent reminder that we can’t and shouldn’t make assumptions about someone’s intent or purpose with their online tree. I’ve heard from many people who are angry about inaccuracies they find in other people’s trees. But we can’t know their purpose, and therefore, it really isn’t our place to judge.

However, it is a fair argument that a good practice would be to clearly mark these exploratory trees accordingly to deter other users from blindly copying and replicating the inaccurate information. An easy way to do this is in the title or name of the tree. For example, a tree could be titled “Jonas Smith Tree UNPROVEN”.

Creating multiple, limited trees can be an effective strategy for conducting targeted online research that only generates hints and connections for those ancestors that you are interested in at the current time.

And remember, you can remove any of your trees at any time. For example, you can delete an exploratory tree that has served its purpose and helped you prove or disprove a relationship.

Plan Now for Success

A family tree can seem like a simple thing, but as you can see there’s more to it than meets the eye. A bit of planning now can ensure that your family tree stays healthy and growing.

About the Author

Lisa Louise Cooke is the Producer and Host of the Genealogy Gems Podcast, an online genealogy audio show and app. She is the author of the books The Genealogist’s Google Toolbox, Mobile Genealogy, How to Find Your Family History in Newspapers, and the Google Earth for Genealogy video series, an international keynote speaker, and producer of the Family Tree Magazine Podcast.

Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links and Genealogy Gems will be compensated if you make a purchase after clicking on these links (at no additional cost to you). Thank you for supporting Genealogy Gems!

by Lisa Cooke | Apr 21, 2016 | 01 What's New, Conferences

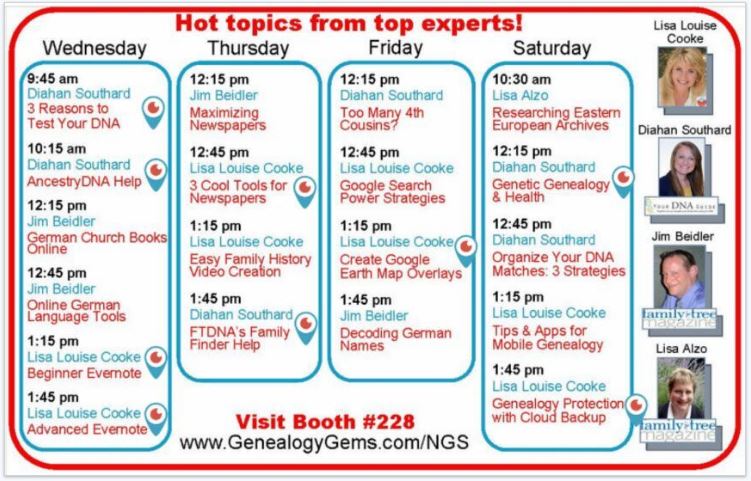

NGS 2016 live streaming options have expanded this year–and include FREE Genealogy Gems classes you can watch on your mobile device wherever you  are.

are.

Can’t make it to NGS 2016? You’re not the only one! You can still join the fun, though–and for free. Lisa Louise Cooke will be live-streaming several lectures from the Genealogy Gems booth “theater” in the Exhibit Hall at NGS from May 4-7, 2016.

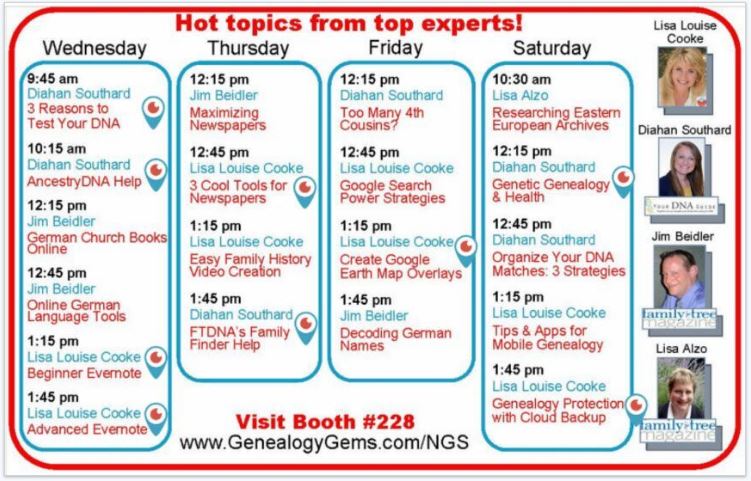

Streaming classes are scheduled as follows (so far–more may be added). The time zone for the conference is Eastern standard.

Wednesday, May 4:

9:45 am: Diahan Southard, 3 Reasons to Test Your DNA

10:15 am: Diahan Southard, AncestryDNA Help

1:15 pm: Lisa Louise Cooke, Beginner Evernote

1:45 pm: Lisa Louise Cooke, Advanced Evernote

Thursday, May 5:

12:45 pm: Lisa Louise Cooke, 3 Cool Tools for Newspapers

1:45 pm: Diahan Southard, FTDNA’s Family Finder Help

Friday, May 6:

1:15 pm: Lisa Louise Cooke, Create Google Earth Map Overlays

Saturday, May 7:

12:15 pm: Diahan Southard, Genetic buy medicine online philippines Genealogy & Health

1:45 pm: Lisa Louise Cooke: Genealogy Protection with Cloud Backup

How to watch the free NGS 2016 live streaming sessions from Genealogy Gems

Lisa will stream again through the free Periscope app, which she used for RootsTech 2016. Get the Periscope app in Apple’s App Store or Google Play,  sign up for a free account, and follow Lisa Louise Cooke to tune in. Sign up for notifications in Periscope, and your phone will “ping” when she starts streaming.

sign up for a free account, and follow Lisa Louise Cooke to tune in. Sign up for notifications in Periscope, and your phone will “ping” when she starts streaming.

Click here for the full list of NGS 2016 free Genealogy Gems booth classes, being taught on-site by Lisa Louise Cooke and Diahan Southard from Genealogy Gems and their partners from Family Tree Magazine. More streaming sessions may be added. Be sure to like and follow the Genealogy Gems Facebook page for last-minute additions!

FREE: Watch Classes that Streamed Live from RootsTech 2016

How to Use Your Mobile Device for Genealogy

Powerful Google for Genealogy Search Strategies

It makes me happy that Autumn is enjoying the Genealogy Gems Book Club. We hear from many avid readers who love browsing our list of mainstream fiction and nonfiction picks for family history lovers. As part of our book club, we interview every book club author, too–from beloved novelists like Fannie Flagg to acclaimed journalists, memoir writers, and historians who take their own unique approaches to family history themes. Hear excerpts of these interviews on the free Genealogy Gems Podcast; full interviews run on the Genealogy Gems Premium Podcast, available by subscription.

It makes me happy that Autumn is enjoying the Genealogy Gems Book Club. We hear from many avid readers who love browsing our list of mainstream fiction and nonfiction picks for family history lovers. As part of our book club, we interview every book club author, too–from beloved novelists like Fannie Flagg to acclaimed journalists, memoir writers, and historians who take their own unique approaches to family history themes. Hear excerpts of these interviews on the free Genealogy Gems Podcast; full interviews run on the Genealogy Gems Premium Podcast, available by subscription. Genealogy Gems Service Manager Lacey Cooke loves Overdrive, too. She sent me these four reasons why:

Genealogy Gems Service Manager Lacey Cooke loves Overdrive, too. She sent me these four reasons why:

As a special shout-out to all the free genealogy resources at your library, Lisa Louise Cooke has granted free access for everyone to Genealogy Gems Premium Podcast episode #125. In this episode, Lisa has a full discussion about more free genealogy gems at public libraries with Cheryl McClellan. Cheryl is not only my awesome mom, she rocks professionally as the Geauga County, Ohio public library system staff genealogist!

As a special shout-out to all the free genealogy resources at your library, Lisa Louise Cooke has granted free access for everyone to Genealogy Gems Premium Podcast episode #125. In this episode, Lisa has a full discussion about more free genealogy gems at public libraries with Cheryl McClellan. Cheryl is not only my awesome mom, she rocks professionally as the Geauga County, Ohio public library system staff genealogist!

are.

are.