Blog

Genealogy Gems Podcast Episode 227

Genealogy Gems Episode 227

This episode is all about the biggest announcements coming out of RootsTech 2019. Highlights include:

- All the major announcements from MyHeritage and Ancestry at RootsTech 2019

- Exclusive interview with MyHeritage DNA Product Manager Ran Snir about their newest genetic genealogy tools The Theory of Family Relativity™ and AutoClusters.

Download the Show Notes PDF in the Genealogy Gems Podcast app.

Please take our quick PODCAST SURVEY which will take less than 1 minute. Thank you!

News: Major Announcements Made at RootsTech 2019

Ancestry Announcements:

Historical records:

Ancestry just released over 5 million Mexico Catholic records and 1 million new France Census and Birth, Marriage, Death records and have several U.S. statewide projects underway, from New York to Hawaii. They also released US WWII Draft Cards from seven states. By early next year, the full set of WWII Draft Cards – all 33 million — will be exclusively available on Ancestry and Fold3.

DNA Tools:

MyTreeTags™:

“MyTreeTags™ allows you to add tags to people in your family tree to indicate whether your research on them is confirmed or verified, or to record personal details, like “never married.” You can also create your own custom tags to note that a person immigrated from Denmark or worked as a blacksmith. You can even use filters as you search your tree to see everyone with the same tag. MyTreeTags™ is one way we can help you save time and enrich your ancestor profile.” You can join the MyTreeTags™ and New & Improved DNA Matches beta at https://www.ancestry.com/BETA

New & Improved DNA Matches:

“We have redesigned the DNA Matches experience to help you make more discoveries, faster. Now you can easily sort, group and view your DNA Matches any way you’d like. New features include color coding and custom labeling offering you more control over how you group and view the matches, quicker identification of your newest matches and new ways to filter your matches.

ThruLines™:

“ThruLines™ shows you the common ancestors who likely connect you to your DNA Matches—and gives you a clear and simple view of how you’re all related. When you link your public or private searchable family tree to your AncestryDNA results, new chapters of your family story may be revealed. ThruLines™ will roll out gradually to all customers who qualify beginning today.”

MyHeritage Announcements:

AutoClusters

“A new genetic genealogy tool that groups together DNA Matches that likely descend from common ancestors in a compelling visual chart. This easy-to-use tool helps you explore your DNA Matches more efficiently in groups rather than as numerous individuals, and gain insights about branches in your family tree.”

DNA Quest Now Accepting Applications

“In March 2018 we launched DNA Quest, a pro bono initiative in which we pledged to donate 15,000 DNA kits to adoptees and those seeking to reunite with family members who were placed for adoption. Within a few months, all the DNA kits we allocated for this initiative were sent out. Applicants opened up to us to share their emotional stories of searching, their hopes for future reunions, and the sense of belonging they felt thanks to their participation in DNA Quest…Following the success of the initiative, we have decided now to extend DNA Quest and donate 5,000 additional MyHeritage DNA kits, for free, to eligible participants.”

Digitizing of Israeli Cemeteries Completed

MyHeritage has completed a 5-year project of digitizing every cemetery in Israel. It is now the first country in the world to have almost all of its gravestones preserved and searchable online, with images, locations, and fully transcribed records. They’ve put up all this content for free, too.

FamilySearch and MyHeritage Tree Sync

(LDS members only)

Geni GEDCOM Import

“We are pleased to announce the return of the GEDCOM Import feature to Geni! This has been one of the most requested features on Geni and we’re excited to finally make it available to everyone. GEDCOM is a standard file format used to save, transfer, and transport family tree information. Long-time users may recall that Geni previously allowed users to start a tree using their GEDCOM files, however we disabled this feature in 2011 to avoid duplication of profiles in the World Family Tree. Our new and improved importer has been rewritten to import a few generations at a time, continuing only on branches where there are no matches to existing profiles on Geni.”

“You can now import a GEDCOM file as a new tree, a new branch if you already have a tree, or onto any existing profile on which you have full permissions to edit and add onto. No longer will you need to endure the slow process of adding each individual one at a time to the tree. Now anyone can quickly add trees which didn’t exist before on Geni, saving you valuable time and allowing you to focus instead on new research.”

The Theory of Family Relativity™

“This unprecedented feature helps you make the most of your DNA Matches by incorporating genealogical information from all our collections of nearly 10 billion historical records and family tree profiles, to offer theories on how you and your DNA Matches might be related. If you’ve taken a MyHeritage DNA test or uploaded your DNA results to MyHeritage, this revolutionary technology may offer astounding new information on your family connections.”

GEM: Digging Deep into the Theory of Family Relativity™ with Ran Snir

Ran Snir is the product manager responsible for MyHeritage DNA products. He leads a really talented team of developers and engineers and designers to create and optimize DNA users entire journey. He led the development of the Chromosome browser for Shared DNA Segments feature at MyHeritage DNA, from concept to production and launch.

PRODUCTION CREDITS

Lisa Louise Cooke, Host and Producer

Bill Cooke, Audio Editor

Lacey Cooke, Service Manager

Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, Genealogy Gems earns from qualifying purchases you make when clicking from the links we provide. It doesn’t cost you anything extra but it helps support our free blog and podcast. Thank you!

Canada and Mexico Genealogy Collections Get Major Updates!

Great news for those searching for ancestors in Canada and Mexico! FamilySearch has partnered with Library and Archives Canada (LAC) to publish the 1926 Census of Prairie Provinces, available to search for free online now. Also new this week are massive updates to Ancestry’s genealogical records collections for Mexico, including vital records and Catholic church records.

Featured: New genealogy resource online for Canada

Genealogy Giant FamilySearch has recently announced the online launch of the Historical Canada 1926 Census of the Prairie Provinces. From the press release:

“FamilySearch International and Library and Archives Canada (LAC) have partnered to publish online the 1926 Canadian census of the Prairie provinces. The free database provides a searchable index of 2 million names linked to 45,000 digital pages of the historical regional Canadian census. Search the census now at FamilySearch.org.

LAC provided the digitized images, and FamilySearch created the index. People with Canadian roots can now easily find information about their ancestors who might have lived in the provinces of Manitoba (639,056), Saskatchewan, (820,738) and Alberta (607,599).

About the 1926 Census of the Prairie Provinces

Since 1871, a Canada-wide census has been held every 10 years. However, during the early part of the 20th century, the population of the Prairie provinces expanded rapidly, so there was a need for more frequent population counts in those provinces. It was decided to conduct a census of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta in June 1906 (between the Canada-wide censuses), and every 10 years thereafter.”

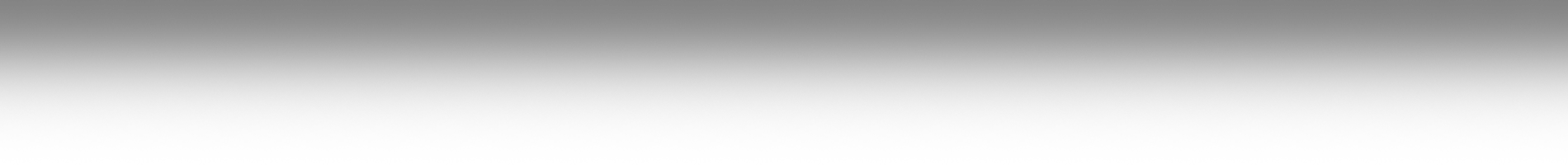

My Great Great Grandfather Found in Saskatchewan!

My Great Great Grandfather Found in Saskatchewan!

We’ve long known that my great great grandfather Harry Cooke immigrated to Canada in 1912, however the trail grows cold quickly from that point. This new collection offered a new chance to track him down in North America. A quick search of this new online database delivered the goods!

Stay tuned to the Genealogy Gems Podcast to hear how to get even more out of the data included in this fabulous collection!

Updated genealogy records collections for Mexico

Ancestry.com has made massive updates to their genealogical records collections for Mexico, listed here by location:

- Aguascalientes Civil Registration Births 1860-1947, Marriages 1860-1961, and Deaths 1859-1961

- Baja California Sur Civil Registration Births 1860-1930, Marriages 1860-1950, and Deaths 1860-1987

- Campeche Catholic Church Records, 1638-1944, plus Civil Registration Births 1859-1921, Marriages 1860-1921, and Deaths 1860-1912

- Chiapas Catholic Church Records 1558-1978, plus Civil Registration Births 1861-1947, Marriages 1861-1952, and Deaths, 1861-1987

- Chihuahua Catholic Church Records 1632-1958

- Coahuila Civil Registration Births 1861-1930, Marriages 1861-1950, and Deaths 1861-1999

- Colima Civil Registration Births 1861-1931, Marriages, 1863-1952, and Deaths 1860-1997.

- Durango Civil Registration Births 1861-1930, Marriages 1861-1951, and Deaths 1861-1987

- Guanajuato Civil Registration Births 1862-1929, Marriages 1866-1929, and Deaths 1862-1930

- Nayarit Catholic Church Records 1596-1967

- Nuevo León Catholic Church Records 1667-1981

- Sinaloa Catholic Church Records 1671-1968

- Sonora Catholic Church Records 1657-1994

- Zacatecas Catholic Church Records 1605-1980

More on researching your Hispanic ancestors

If you have Hispanic heritage — anywhere from Mexico to Chile to Spain — you’re in luck: More resources for tracing their immigration are available more readily than ever before. In this special research collection from Family Tree Magazine, get eight resources to trace your Hispanic heritage for one low price! You will learn important historical dates and timelines, Spanish naming traditions, where to find records of immigration by ship, plane and train, and much more! Get the Hispanic Heritage Research Collection for just $24.99 – a $70.96 value!

Lacey Cooke

Lacey has been working with Genealogy Gems since the company’s inception in 2007. Now, as the full-time manager of Genealogy Gems, she creates the free weekly newsletter, writes blogs, coordinates live events, and collaborates on new product development. No stranger to working with dead people, Lacey holds a degree in Forensic Anthropology, and is passionate about criminal justice and investigative techniques. She is the proud dog mom of Renly the corgi.

Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links and Genealogy Gems will be compensated if you make a purchase after clicking on these links (at no additional cost to you). Thank you for supporting Genealogy Gems!

DNA and Genealogy Records Updates at Ancestry

Ancestry dominates this week’s genealogy news with a new update for AncestryDNA genetic communities! Also new from Ancestry this week are big updates to collections for England and Canada.

Featured: AncestryDNA News

Announced on Tuesday, February 19: “AncestryDNA has launched 94 new and updated communities for customers of African American and Afro-Caribbean descent. These updates mean that in addition to enabling the African American community to dive deeper into their family history, they can also discover how their family connects to historical moments in time, such as the Great Migration–the movement of 6 million African Americans out of the rural South during the mid-1900s.

AncestryDNA can connect members to communities of people who lived and traveled with their ancestors 70-300 years ago–including communities of people who were enslaved in the US and Caribbean then later flourished in the South or traveled northward in the 1900s during the Great Migration.

400 years after the first documented arrival of Africans in the English colonies, Ancestry can map out the forced and voluntary migration patterns of African American and Afro-Caribbean communities, then connect their descendants to that history using their DNA.

These new insights, provided using our unique Genetic Communities™ technology, can reveal the roles and unique impact your ancestors played in history. Ancestry’s unmatched combination of the world’s largest consumer DNA network and millions of family trees allows our customers to see this level of precision and trace how their ancestors may have moved over time.”

New and Updated English Genealogy Collections

If your ancestors hailed from England, you will love these new and updated genealogy records that Ancestry has added to their collections!

New: London, England, Poor Law Hospital Admissions and Discharges, 1842-1918 — After the Poor Law Act of 1834, workhouses became the main vehicle of assistance for the poor. Conditions were very hard and many of those who entered workhouses needed medical care. Infirmaries attached to workhouses, and administered by the Poor Law Unions were used to provide some relief for the impoverished elderly, chronically ill and anyone who suffered from one of many ailments prevalent at the time. You might find your ancestor’s name, admission date, age, death date, discharge date, and Poor Law Union.

Updated: London, England, Selected Poor Law Removal and Settlement Records, 1698-1930 — The records in this database relate to settlement and removals in the unions of Bethnal Green, Hackney, Poplar, Shoreditch, and Stepney. They include examinations and settlement inquiries, registers of settlement, orders of removal, and other documents. Details included in these records vary widely, depending on the document. An order of removal may contain a name, age, current parish, and parish being removed to. A settlement register may note number of children and marital status.

Updated: London, England, Poor Law School District Registers, 1852-1918 — These records are made up of lists of children who were admitted to and discharged from District schools across London. When education was required, children could be discharged from their schooling if they were needed to work to help support the family. The records vary by school and some are more detailed than others.

Updated: Somerset, England, Church of England Baptisms, Marriages, and Burials, 1531-1812 — This database includes records with dates ranging from 1531 up until 1812, after which George Rose’s Act called for preprinted registers to be used for separate baptism, marriage, and burial registers as a way of standardizing records. See the browse on the right to determine which parishes are included in this collection and the date coverage for each parish.

Updated Ontario, Canada Genealogy Records

Ancestry has also made updates to their vital records collections for Ontario, Canada! Discover your ancestors in the updated collections noted below.

Ontario, Canada Births, 1858-1913 — This database is an index to over 2 million births that were registered in Ontario between 1869 and 1913. Each name is linked to an image of the actual birth register or certificate in which the individual was recorded. Additional information may be found on the image that is not included in the keyed index.

Ontario, Canada, Marriages, 1826-1937 — This database is a collection of approximately 3.3 million marriages recorded in Ontario, Canada between 1826 and 1937. Additional information may be found on the original record. Be sure to view the corresponding image, if there is one available. If no online image is available, be sure to use the information found in this database to locate your ancestor in the original records that the index references – more information is usually available in the records themselves than is found in an index.

Ontario, Canada, Deaths and Deaths Overseas, 1869-1947 — This database is an index to over 2 million deaths that were registered in Ontario from 1869 to 1947. The database also includes deaths of Ontario military personnel overseas from 1939-1947. You might discover your ancestor’s name, death date, estimated birth year, birthplace, and Ontario county of death.

Bring your story to life at Ancestry

Ancestry has always been one of the genealogy giants in the family history community, and they continue to be one of the largest databases in the world for genealogists. With over 10 million DNA profiles, billions of records, and millions of family trees, it’s a goldmine of genetic and genealogical matches for you to discover those hidden ancestor gems. Start with a free trial, take a DNA test, or upload a tree to get started today.

Lacey Cooke

Lacey has been working with Genealogy Gems since the company’s inception in 2007. Now, as the full-time manager of Genealogy Gems, she creates the free weekly newsletter, writes blogs, coordinates live events, and collaborates on new product development. No stranger to working with dead people, Lacey holds a degree in Forensic Anthropology, and is passionate about criminal justice and investigative techniques. She is the proud dog mom of Renly the corgi.

Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links and Genealogy Gems will be compensated if you make a purchase after clicking on these links (at no additional cost to you). Thank you for supporting Genealogy Gems!