Elevenses with Lisa Episode 37 Show Notes

There’s a very important story behind each one of your genealogy records. In this video and article we discuss why it’s critically important to understand the provenance of each record. We also talk about specific things to look for as you analyze their meaning. Great genealogy research requires a great understanding of the story behind your genealogy records! Keep reading for the show notes that accompany this video.

The story behind your records includes many important areas to be considered:

- Provenance / History

- The reason for the record

- Information source (primary vs. secondary)

- Motivating factors of the informants

Let’s take a look at each of these.

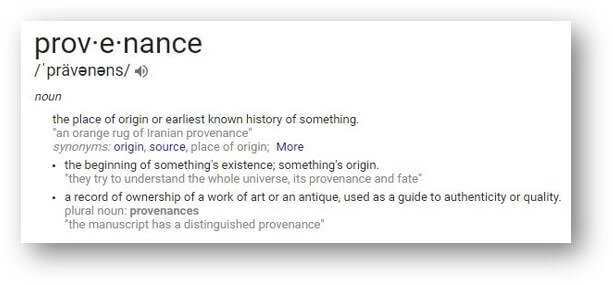

Provenance

In the art world, knowing the provenance of a piece is crucial to understanding its value.

Provenance looks at an object’s origins, history, and ownership. Investigating and analyzing the provenance of a piece can shed light on:

- whether the piece is authentic,

- whether it truly was created by the attributed artist in the stated timeframe,

- What the value of the item might be.

Elevenses with Lisa Episode 37

The principle of provenance is true for genealogical sources, too.

The Story Behind the Records

Provenance is important because it helps us determine how much weight to give the information provided by the genealogical record.

We need to ask When and where was the record created? We are looking for:

- Records created closest to the time of an event

- Documents created in places associated with your relatives

- Documents created by people who knew them or were authorities

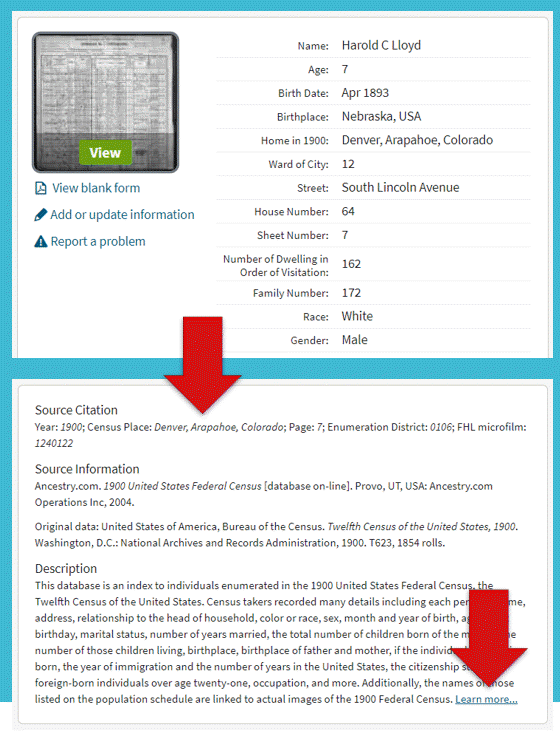

Review the Record’s Source Information

It’s important to take the time to review the available source citation information for each record we use. Fortunately, many genealogy websites that provide access to the records of our ancestors also provide critical background information about that record. This can help us find the answers to our questions and help us evaluate how much credence to give the information.

Scroll down and click through to get the rest of the record’s story.

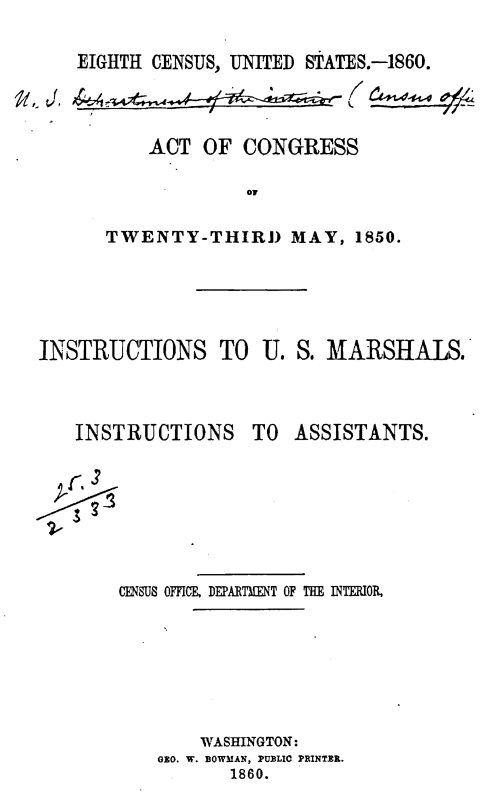

Sometimes it just takes a little digging to uncover the backstory on a record. For example, the census enumerators received detailed written instructions before being sent out into our ancestors’ neighborhoods to collect data. You can review digitized copies (or transcriptions) of those instructions at the United States Census Bureau website for all years of the decennial census except 1800 through 1840.

1860 Census Enumerator Instructions

Finding Aids

Whether you’re researching at home or in an archive, look for or ask for the finding aid or reference guide for the collection you are using.

A finding aid may include the following sections:

- provenance

- how the materials were used

- contents / physical characteristics

- restrictions on use

- scope and contents note, summary and evaluation

- box or file list

Learn more about Finding Aids in Elevenses with Lisa episode 31 featuring the Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center. It includes a discussion of finding aids.

Genealogy Gems Premium subscribers: Learn more from a professional archivist about using finding aids in Premium Podcast episode #149. (Membership required. Learn more here.)

The same holds true for objects that are passed down through the family, whether it be a family Bible or a transcript of a reminiscence you find online.

Resource: Elevenses with Lisa episode 29.

Records as a Whole

Whenever possible, consider a source as a whole. It’s tempting to want to zero in on the paragraphs or photos that interest you most, but you may miss out on important information that changes what this source has to tell you. For example, the specific placement of a photo in an album can be as significant as the printed photographic image. A photo’s position can indicate the relationship of the people in the photo to others on the same page, or the timeline of events.

Does the record appear complete?

Take note if any part of the source appears to be missing or illegible, especially if it appears that some of it has been deliberately removed, erased, or crossed out.

You may be able to make more sense of the partial information—or take a guess at why it was removed—as you learn more about the family. There may be a perfectly innocent reason for the change. But you may also be seeing evidence that someone who wanted to erase unpleasant memories or conceal a scandal.

Where has the item been over the years?

Where the source has been kept over time and who possessed it is an important part of provenance. Try as best you can to reconstruct and document the chain of custody of the item.

Resource: Heirloom Tracking Template

My Heirloom tracking page helps you document the complete story behind your precious family heirlooms. Premium Members can download the template from Elevenses with Lisa episode 6.

Is the record the original?

Whenever possible, consult the original version of a genealogical record. Indexes, typed-up copies, or abstracts may not be as complete or accurate. Remember, handwritten or typed copies of older originals may have been made in the days before photocopying technology.

The Story Behind the Document: Motivating Factors

Another important question to ask about a record is Why was the record created? Understanding the motivation of the person, organization or governmental agency creating the document can help you anticipate their possible bias. It can also provide clues regarding information that you would expect or hope to find, but don’t. While the information may seem important, it may not have fallen within the scope of the original intent. Therefore, you may need to look for additional records that can help fill in the gaps.

Tax lists provide an excellent example of why we need to understand the motives and scope of the records we use. When reviewing a tax list, we need to determine if the government was taxing real or personal property and if it was including every head of household or just adult males.

Why was the information provided?

The original purpose of a source is highly relevant to how much faith you put in its contents. Here are a few examples of why the information provided might not be totally accurate:

- A woman might have altered her testimony in divorce proceedings in an effort to minimize damage to her own reputation and future.

- Newspaper articles may be filled with a variety of biases by the author, publisher, or those being interviewed.

- A man may have lied about his age or citizenship on a draft card, either to avoid military service or in order to be included despite being underage.

Comparing the record with similar records can help reveal where the truth lies.

Who was the informant?

The information on a record is the person who supplied the information. Sometimes this is the same person who created the record, such as the writer of a diary. In the case of a U.S. census, the informant is the person in a household who told the census enumerator about the people who lived there. In many cases, it’s impossible to know who the informant was. Thankfully in 1940, census enumerators were instructed to mark the informant with a circled “X,” as shown in these two households. This is just another example of the value of doing

Reliability of Informants

A source may have multiple informants. Each may have had unique knowledge of the situation. For example, on a death certificate a relative may provide the personal information while a physician provides the death-related information.

If the informant shares the deceased’s last name they:

- likely are a relative

- likely had first-hand knowledge of the deceased’s marital status, spouse’s name, and occupation.

- (if father or brother) likely have provided primary information relating to the deceased’s birth, and parents’ names.

Even when a relative is close, we need to stop and think about whether they knew the information because they experienced it first-hand or were told about it. For example, if the informant was the deceased’s father, the information about the deceased’s mother (his wife) such as birthplace would actually be secondary since he presumably wasn’t present when she was born! And that leads us to understanding the difference between primary and secondary sources and information.

Primary & Secondary Information

Historical evidence can either be considered primary or secondary information. Genealogical scholar Thomas W. Jones defines these terms in his book, Mastering Genealogical Proof:

- “Primary information is that reported by an eyewitness. Primary information often was recorded soon after the event, but it may be reported or recorded years or decades later.

- Secondary information is reported by someone who obtained it from someone else. It is hearsay.”

Interestingly, the same document can include both primary and secondary information. It helps to think in terms of primary and secondary information instead of striving to designate the source document as primary and secondary.

How do all these clues add up?

It’s clear that as genealogists our goal is not only to evaluate each family history source, but also each piece of information it provides. Asking the right questions helps us ultimately answer the all-important question: how much do you trust what this record is telling you?

Answers to Live Chat Questions

One of the advantages of tuning into the live broadcast of each Elevenses with Lisa show is participating in the Live Chat and asking your questions.

From Debra L.: Is the book (A Cup of Christmas Tea) good to give to 12 year old tea lover?

From Lisa: It has a wonderful message for any age of caring for others in the family, especially older relatives. (It’s not really about the tea 😊)

From Mary P.: As custodian of my parents’ life memorabilia I need help with the 5ish address books. Can you suggest an attack plan to glean information, what to store/record\research online etc. ? I’m overwhelmed.

From Lisa: It’s really a matter of how much time you have. I would lean toward transcribing them into Excel spreadsheets that can then be searched and sorted, including a column to indicate the relationship (friend, co-worker, relative, etc.) Store the books in an archival-safe box like this one.

From Mary P.: I’m back, can you help with this project? My grandfather built two houses in Garwood, NJ about 1920. I’d like to find information on their construction and owners/renters over time.

From Lisa: Elevenses with Lisa episode 20 & episode 28 have everything you need!

Elevenses with Lisa Archive

Premium Member have exclusive access to all of the archived episodes and downloadable handouts. Visit the Elevenses with Lisa Archive.

Get My Free Newsletter

Get My Free Genealogy Gems Weekly Email Newsletter

The newsletter is your guide to upcoming shows, articles, videos, podcasts and new Premium content.

Resources

Bonus Download exclusively for Premium Members: Download the show notes handout.

Become a Genealogy Gems Premium Member today.

Please leave your comment or question below

Let us know if you found this video and article helpful. And if you have any questions, don’t hesitate to ask. We’re here to help!

Lisa, very good reminders of how to evaluate the records/information that we find in our research. Thank you.

I do have a question: I am editor of the Geauga County (Ohio) Genealogical Society’s quarterly newsletter, the Raconteur. I’d like to print this article in the next issue as I’m sure it would be of help to our members. Do you give permission for reprinting your articles? Thank you again.

Hi Jan, I would be delighted. Please visit https://lisalouisecooke.com/article-archive/ for details on attribution. Thanks!

Lisa,

I will be praying for your daughter and your family. I wish her a complete and speedy recovery. Hopefully, the new year will be a healthier and happier one than 2020.

We still miss you at SRVGS. We worked together on “speakers” many years ago and I follow you thru the genealogy networks and your blog. A Merry Christmas!!! Rae Atwood

Hi Rae, so nice to hear from you! Yes, I remember working together and I hope you’ll say “hi” to all at SRVGS for me. And thank you for your well wishes. My daughter is doing better each day.

Hi Lisa, this is a very timely topic. Can you do a review or mention abt Ancestry’s new DNA “discovery” Story Scout? (Maybe you’ve already done it & I missed it). I think this is a way for Ancestry to draw in new paying customers, but is very misleading to the newbie genealogists, since it shows pictures and makes generalities that may not necessarily be abt YOUR ancestor since it apparently relies a lot on Public Trees (which we all know are not done very well) for a lot of the linking information